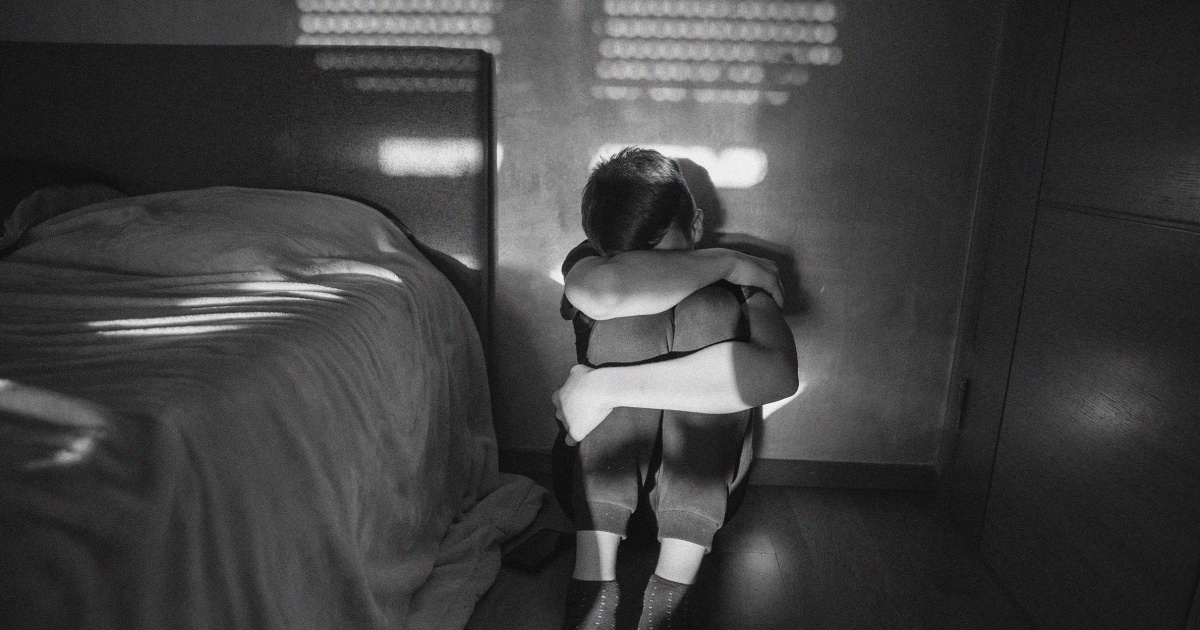

Hospitalizations and emergency room visits for suicide attempts and ideation rose nationally among children and teens from 2016 to 2021, a new study has found — the latest in a series of alarm bells about the state of young people’s mental health.

According to the research, published Wednesday in the journal JAMA Network Open, nearly 66% of the cases were girls, and the average age was 15. The study also revealed seasonal trends: ER visits and hospitalizations were 15% higher in April and 24% higher in October than the January rate, which the study used as a baseline because it was close to the annual average. However, 2020 was an exception both to the seasonal fluctuations and the increase in suicidality over time.

Taken as a whole, the researchers said the findings indicate that the academic calendar may affect youth mental health.

“If you are a health care provider or a public health official looking to put dollars or interventions towards in school programs, focusing on females, particularly during the seasonal patterns, might be an effective way to reach the individuals who are at greatest risk,” said Scott Lane, a psychiatry professor at UTHealth Houston and co-author of the study.

Other recent research has similarly shown a rise in mental health challenges among youth, particularly adolescent girls. A 2021 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention survey found that nearly 57% of teen girls reported feeling “persistently sad or hopeless,” and 22% of teens said they had seriously considered dying by suicide. Even before the pandemic, the CDC reported that 1 in 5 teenagers had experienced an episode of major depression.

The new study did not look at deaths by suicide, which is the second-leading cause of death among adolescents, according to the CDC. Between 2007 and 2018, the suicide rate among people 10 to 24 years old increased by 57%, though the rate is higher for most other age groups.

The new research instead focused on a set of more than 73,000 emergency room visits and hospitalizations for suicidal ideation or suicide attempts among children and teens enrolled in commercial health insurance plans and in Medicare Advantage. The participants were between 10 and 18 years old, and the results showed that between 2016 and 2021, these hospital visits jumped from 760 out of every 100,000 people studied, to 1,160. The 2020 number, however, dropped to 942.

That dip may have been because people were hesitant to visit hospitals due to Covid risks, Lane said.

Another possible explanation could be that during lockdowns, some teachers were more lenient with schoolwork, students were sleeping more and some teens faced less anxiety about being excluded from social gatherings, according to Jonathan Singer, a professor of social work at Loyola University Chicago and former president of the American Association of Suicidology, who was not involved in the research.

“A lot of adults forget that kids spend all day going from one place to the next, one subject to the next, surrounded by people they didn’t choose to be with, asked to do things they never chose to do,” Singer said. “I think that there is a stressor related to that which we often discount.”

Lane said the jump in 2021 was larger than his team would have predicted.

“The negative mental health effects of the Covid period — we may have simply uncovered those post-Covid, when there was a return to school,” he said.

The seasonal spike in suicide ideations and attempts that his study found, Lane added, is a well-researched trend across age groups, often attributed to seasonal changes in temperature and weather.

But children and teens in particular, Singer said, may be more likely to feel optimistic during the beginning of the school year, then see their mental health suffer by mid-fall. In many cases, he added, students are also monitored more closely for mental health-related behavioral issues at school. Plus, fall and spring months can coincide with placement exams or standardized tests, Singer said.

“Now that we know that there’s some national data suggesting that hospitalizations increase during the fall and the spring, we need to think about doing suicide prevention programming both right at the beginning of the school year, but also thinking about doing it kind of proactively when kids are younger,” Singer said.

Regina Miranda, a psychology professor at Hunter College who was not involved in the study, said sending teens with mental health challenges to hospitals or medical facilities is often a poor solution to the problem. Instead, she said, more should be done to reduce the stigma about depression and suicide and to improve access to mental health counseling and support.

“When a kid says that they’re thinking about suicide, sometimes the tendency is to elevate the level of risk of that child because people are concerned,” Miranda said. “But automatically taking the kid to the hospital, to the emergency room, for some kids that might be helpful, but not for many kids, that’s not the next necessary step.”

Miranda also pointed out a gap in the study: The data set did not include patients who were uninsured or covered by Medicaid, a group likely to come from marginalized backgrounds.

Overall, Miranda said, a shift is needed in the conversations that school administrators, counselors and parents have with young people about their mental health.

“We have to start thinking about it not in an alarmist way, but in a way that will encourage kids to feel comfortable disclosing to people that they’re thinking about suicide — where we can normalize having conversations about mental health in school without treating people who are struggling with their symptoms as if there’s something wrong with them,” Miranda said.

If you or someone you know is in crisis, call 988 to reach the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline. You can also call the network, previously known as the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, at 800-273-8255, text HOME to 741741 or visit SpeakingOfSuicide.com/resources for additional resources.