The boy couldn’t have been older than six or seven. Brown hair with a streak of bright orange. It was 2003, and Geoffrey Ling, a young Army doctor, was looking down at a new patient who’d arrived at his medical unit in Afghanistan missing a hand.

The Soviet Union during its long and ultimately losing campaign to quell the restive corners of the country had taken to dropping thousands of land mines out of the back of helicopters. Like little butterflies, the mines would twist and flit to the ground, a bright green that would fade to gray with time.

Almost daily, Ling would stare down at a child who had answered the siren call of the toy-like miniature bombs. A boom, a lost appendage, and they’d find their way to Ling, who’d be tasked with patching them up for a life where the best prosthesis still relied on hooks and pulleys.

Read Next: Bowe Bergdahl’s Sentence Is Thrown Out by Judge as Case Takes New Turn

The limited options got Ling thinking. What if he could come up with a better way to make an artificial hand respond to the whims of the brain, maybe by connecting the two? He’d been approached by the Pentagon’s pie-in-the-sky research wing, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, or DARPA, shortly before he left for Afghanistan, so when he got back, he started what would become a decades-long march to make the connection between brains and computers possible.

What started as theoretical research quickly took on greater relevance when scores of service members began facing roadside bomb attacks in Iraq in the following years, leaving many missing limbs. All of a sudden, the concepts Ling had been contemplating became a national priority.

Early on, scientists realized that the same medical research that would allow them to make prosthetics respond to the brain might also be used to enhance how troops fight, such as special operators communicating on the battlefield without uttering a word, interacting with a drone, or maybe even helping eradicate the fear of entering a room filled with enemies and the post-traumatic stress that can follow a firefight.

If you can understand the signals within the brain — a task entirely impossible before the advent of artificial intelligence, which allows the digestion of massive data sets, you might be able to alter them, or otherwise change the nature of the closed system the brain had been since humans developed oversized thinking lobes.

“Now, you think about the what-ifs. That was very clear. Collect the brain signals, get the robot arm, clear use case, show the science can be done,” Ling told Military.com in a 2021 interview. “Now what’s next? Well, what’s next is where does your imagination take you?”

Ling described how early on the laboratory conducting the research connected one patient to a flight simulator instead of a robotic arm. Using just her brain, she was able to achieve liftoff on the screen.

“When you talk to her, and you ask her what she’s doing, she’d go, ‘Oh, I think I want to fly. I think about looking up, and the plane goes up,'” Ling detailed. “She’s not thinking about moving a joystick or a rudder, she’s thinking about flying, and the plane flew.”

The potential medical applications of access to the brain for treating ailments are far-ranging, but pressure to compete with America’s adversaries might tempt leaders with the next step: enhancement.

The fear of being surpassed by “near-peer” competitors — Pentagon parlance for Russia and China — is driving all kinds of technology pushes by the military, including hypersonics, artificial intelligence and bioenhancement.

Both China and Russia can move at an expedited pace when it comes to military research due to their authoritarian government structure, and both have different standards when it comes to ethical guidelines in medical testing.

“There’s a very real set of scenarios where neurotechnology plays a role in our national security moving forward,” Justin Sanchez, the former director of DARPA’s biological technologies office, told Military.com in a 2020 interview. “We cannot lose sight of that. It has to be a priority for us.”

In the 20 years since Ling began work on what scientists call brain-machine interface, the ability to understand and even alter the brain has progressed rapidly. What started as a discovery to heal the wounds of war kick-started research designed to make America’s warfighters more efficient and more lethal in battle.

The Air Force is testing how hand-held devices and skull caps that use electrical current to stimulate the brain could help pilots learn more efficiently and get into aircraft cockpits faster. DARPA has also funded tests using electrical currents funneled through electrodes implanted in the brains of those suffering from epilepsy, piggybacking on a recognized treatment to see what else the currents could do.

DARPA’s Restoring Active Memory program was launched in November 2013 with the goal of “developing a fully implantable, closed-loop neural interface capable of restoring normal memory function to military personnel suffering from the effects of brain injury or illness.”

By 2018, DARPA announced it was working with researchers at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center and the University of Southern California to actually implant devices in “neurosurgical patient volunteers who were being treated for epilepsy” and found the technology gave a boost to natural memory function, according to a press release.

Early results from the testing showed the ability to substantially alter the mood of patients with targeting stimulation.

A year later, in 2019, a report from the Army’s Combat Capabilities Development Command predicted that brain enhancement technology, particularly in the form of implants, could be common by 2030.

“As this technology matures, it is anticipated that specialized operators will be using neural implants for enhanced operation of assets by the year 2030,” the report details. “These operators will include teams from the Special Forces, military pilots, operators of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) or unmanned surface vehicles (USVs) such as drones, and intelligence personnel.”

That means that in less than a decade, if the technology experts are right, the Pentagon could be using brain implants for troops, special operators and pilots to be connected to technology.

But while the technology is advancing, neuroethicists, futurists and medical researchers are asking whether the military is ready for the responsibilities entailed with messing around in people’s heads. These experts have told Military.com in more than a dozen interviews that the brain is so incredibly complicated and the technology is so new that we don’t fully understand the implications.

“The brain is, arguably and ironically, the most complex, least understood technology that there is, and that is the fundamental problem and opportunity that we’re wrestling with here,” Peter Singer, a scholar on 21st century military technology and an author who focuses on the future of warfare, told Military.com in an interview.

If DARPA’s technology ever becomes a device that is implanted in the brain of a warfighter, what responsibility would the government have for maintaining that technology? Will the Department of Veterans Affairs be servicing degrading brain implants for decades after young Americans take off the uniform? Will mental health or cognitive disorders emerge decades from now, and will those who suffer them receive care?

“I would say the government has a huge responsibility,” Dr. Paul Appelbaum, one of the country’s leading scholars in legal and ethical issues in the medical field, told Military.com. “They have introduced into this person’s head — whether they’ve done it invasively or noninvasively — a technology that was designed to change their brain function. And by intervening in that way, I think they have created a responsibility to follow these people down the road and try to ensure that adverse consequences don’t result from their participation.”

Special Forces, Super Soldiers

One of the DARPA programs that showed early promise in the 2010s, Systems-Based Neurotechnology for Emerging Therapies, involved testing how implants inside of brains might be helpful for altering moods. The program targeted the creation of a device that could regularly provide stimulation to manage patients’ conditions — partially inspired by the ongoing issues helping veterans combat the trauma of war.

Given the ethical concerns tied to fishing around in people’s heads, the subjects for the research were a group of patients already due to have electrodes implanted to combat epilepsy. But while doctors were in there, they agreed to let researchers test out how stimulation from inside the brain might make them feel.

“There’s one patient that stands out in particular, a relatively young woman, very personable. This was actually the second time she’d had to have brain surgery for epilepsy,” said one of the researchers, who spoke to Military.com on the condition of anonymity because they did not have permission to discuss the program.

The researchers didn’t tell the patients when they would be using the stimulation, to prevent the placebo effect, instead maintaining a running dialogue. This particular patient suffered from severe anxiety.

“We said, ‘Are you feeling different right now?’ She said, ‘I feel great, I feel energized,'” the researcher recalled. “I said, ‘Oh, is this something you sometimes feel or do you never feel like this?’ And she said, ‘Oh, this is me on a good day. This is the way I want to feel.'”

That kind of shift in mood could be revolutionary for veterans suffering from the bonds of post-traumatic stress, if the technology proves viable.

Brain implants, if that’s where the research leads, wouldn’t stand as the first time the government has overseen and serviced devices in bodies.

The closest equivalent might be how the VA monitors pacemakers — a medical device that sends electrical signals to the heart to help it keep its rhythm and function.

A 2020 Veterans Health Administration’s directive ordered all VA patients with pacemaker-type devices to enroll in its National Cardiac Device Surveillance Program, which diligently keeps tabs on battery levels, heart health and other problems that may arise with the technology.

Subsequent virtual or in-person appointments can be scheduled, depending on what work needs to be done. As of 2019, American Heart Association research says that nearly 200,000 veterans have these devices monitored through the VA.

But pacemakers have been in use since the 1950s, a well-understood technology where VA doctors can follow decades of medical research.

There are other historic examples of military technology that have, over time, been shown to cause harm, often when rolled out with less scientific rigor. Agent Orange — a Vietnam War-era herbicide that was contaminated with dioxin during the production process — was eventually linked to leukemia, Hodgkin’s lymphoma and various types of cancers in service members. What was once quickly sent to the battlefield to provide a tactical advantage later turned into a health nightmare.

The brain is the human body’s most sensitive and complex organ. Side effects of high-risk surgeries and electric stimulation are constantly being evaluated by the medical community. But there are some people, who despite not knowing all of the potential problems that could one day be discovered from this technology, are eager to try it out if only for the slightest tactical advantage.

Elite warfighters — the Navy SEALs, the Army Green Berets, Air Force special warfighters and Marine Corps‘ Raider Regiment — are already experimenting with electrical stimulation delivered through the surface of the head. Due to the long-standing culture within those units, often accompanied with gallows humor about dying young and pretty, they’ll do whatever is necessary to become, and stay, the most lethal men and women in uniform.

“That community, by and large, is all about improving human performance,” said an Army Special Forces officer, who spoke to Military.com on condition of anonymity because he’s not authorized to speak to the media. “From some perspective, they’re always trying to push us to a more lethal edge.”

And for a community facing deep-seated issues from decades of intense operations, the prospect of being able to alter not only how the brain reacts from a tactical standpoint, but also how it might react emotionally, holds enormous appeal.

“I think some guys would be scared or hesitant, but if you’re telling me I could go into a room and not have the same stresses and worries confronting an enemy, I’d have a really hard time not signing up for it either,” the Army Special Forces officer said. “You’re going to see a line outside the door, especially if it’s a drastic improvement.”

Chris Sajnog, a Navy SEAL who served for 20 years and is now a master training specialist, told Military.com that the possible applications of such technology to train better or maybe even eliminate mental barriers such as post-traumatic stress disorder present a unique dilemma.

As medical researchers, and even DARPA, look at how this technology could be used to help with PTSD, memory loss and depression, Sajnog wonders about the unintended consequences.

Part of what bonds special warfighters together are the horrors and stresses they see in conflict. And, Sajnog said, that’s part of the reason that units like the Navy SEALs train so hard. Being able to potentially wipe those traumas away changes the dynamic of what brings that team together.

But Sajnog said he’s having a hard time not supporting an innovation that could one day get rid of debilitating mental health problems.

“The stress that we endure together is what makes our bond so special and so different from other units,” Sajnog said. “But if it gets to a point where people are having anxiety and stress, I think you can look at ways to reduce that.”

Some special operators also voice concerns that such technology, especially if it’s used to alter moods and behaviors, could make deployments more frequent. If the men and women aren’t complaining or are more numb to the frequent combat they are experiencing, military leadership would have a hard time standing them down.

Training the Brain

The device is pressed under the chin, like a knife held to the jugular of a hostage in a Hollywood action movie. The user slowly dials up the electricity coursing toward their brain, triggering muscle contractions in the neck that creep upward.

Once the lower jaw starts vibrating, and the lip pulls slightly to the side from the current, it’s time to switch off the device and focus on learning how to be a pilot.

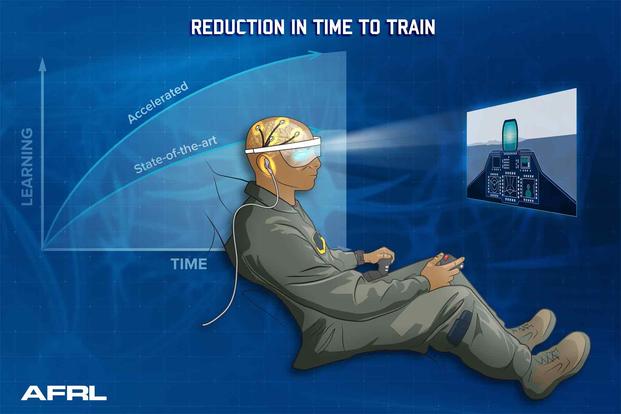

The voltage is part of a program at the Air Force Research Laboratory designed to help cut pilot training time in an era where the service is struggling to find and retain airmen capable of flying.

Andy McKinley, who runs the testing of brain stimulation that’s part of the Individualized Neural Learning System, known as iNeuraLS, which kicked off in 2020, has been studying the effects of electricity on the brain for more than a decade and a half.

“There’s always a lot of variability in any physiology signal,” McKinley said in an interview. “Your current brain state matters. If I’m trying to enhance your attention and arousal, but you’re already super amped up, I’m either not going to have an effect or it may decrease your attention. … People say they feel more alert, but not jittery.”

McKinley said he’s heard anecdotally about the positive effects some special operations airmen have had with stimulating their brains.

“There was one guy down there at AFSOC [Air Force Special Operations Command], who said he was highly addicted to caffeine. He had to have energy drinks and coffee all day long to stay awake,” McKinley recalled. The special operator started using a device called a gammaCore, which sends electronic signals to the brain to feel more alert.

“So using that, he completely got off caffeine, didn’t feel like he needed any caffeine anymore.”

In the early 2010s, McKinley co-authored several research papers suggesting that zapping brains might help speed up learning, something researchers had initially seen in animal studies but had only just begun to consider for people.

The program involves electric stimulation and monitoring of the impact that stimulation is having on the brain so that it can be adjusted. That involves both miniaturizing brain scanning technology like MRI machines so that they’re small enough to be wearable — hopefully tucked into a hat — and using advanced artificial intelligence to decipher the meaning of the brain signals those scans detect, as no two brains are exactly alike.

The early data from McKinley’s studies show an improvement in learning, with people retaining roughly 20% more information initially, and 35% more 90 days on from the training. “The processes that are occurring under the hood with this type of stimulation [are] the same that would be occurring with a lot of practice. It’s just that we’re speeding up that natural process.”

If the technology proves successful, the Air Force has plans to see how else it could use this variety of brain enhancement.

“We’re starting with the use case of a pilot training, but the idea is to expand that to a variety of other types of training,” McKinley said.

What makes this approach so appealing is that it doesn’t require implanting devices in the brain, a high hurdle for any medical program. By using stimulation from outside of the skull, McKinley’s team is starting to see performance enhancement that would be a much easier sell to many service members.

Implanted devices that stimulate the vagus nerve, the same neural tunnel from the lower part of the brain down through the neck and chest to the stomach that is zapped externally by the Air Force team, have received FDA approval for some methods of stroke rehabilitation; devices used outside the skin have been approved by the FDA for migraines and headaches, according to the Mayo Clinic.

Side effects from an implanted vagus nerve stimulation device can include voice changes, throat pain, headaches, trouble swallowing or tingling or prickling of the skin, according to the Mayo Clinic. Side effects observed thus far for the hand-held devices are minimal, often relating to slight pain or irritation from too much stimulation.

Transcranial direct current stimulation — sending electrical signals to the brain through the scalp as military researchers are also testing — saw some reported side effects such as some itching, burning, tingling, headache and other discomfort, according to the National Library of Medicine.

The Air Force Research Laboratory’s experiment with pilot training is one of the most public-facing applications of neuro-enhancing technology, but only one small demonstration of the technology that DARPA has been advancing for years. Programs like N3, that sought to create a brain-machine connection without implantation, have been undertaken alongside more invasive approaches like the mood-altering current tests using implants.

So far, science hasn’t advanced enough to make some of the wildest dreams of researchers come true, like being able to easily control battlefield weapons systems directly from the brain or enhancing human senses. The brain is still too complicated, and deciphering what specific electrical signals signify is still too daunting. But talking to key researchers, it’s clear it’s where the agency wants to go.

Global Competition Heating Up

Even if a surgical knife isn’t taken to skulls, it’s unclear whether harm might still be done to America’s service members if electronically stimulating the brain becomes commonplace. The technology is just too new.

But the pressure to gain an edge over international competitors such as China and Russia continues to push the research forward, both in the U.S. and overseas.

“China has even conducted human testing on members of the People’s Liberation Army in hope of developing soldiers with biologically enhanced capabilities,” former U.S. Director of National Intelligence John Ratcliffe wrote in The Wall Street Journal in 2020. “There are no ethical boundaries to Beijing’s pursuit of power.”

In late 2021, the U.S. Commerce Department’s Bureau of Industry and Security sanctioned the Chinese Academy of Military Medical Sciences and 11 of its research institutions because its research posed “a significant risk of being or becoming involved in activities contrary to the national security or foreign policy interests,” including development of “purported brain-control weaponry.”

In 2021, prior to the invasion of Ukraine, Russia’s Kommersant Business Daily reported the government approved a program to research controlling electronic devices with the use of the human brain by implanted computer chips. President Vladmir Putin reportedly personally approved the project. A Kremlin spokesman later said he could neither confirm nor deny the report, according to Tass – A Russian state-owned news agency.

But troops taking part in medical research is often morally tricky. Some ethicists have questioned whether a service member, whose primary responsibility is to follow orders, can fully participate in a brain-computer-interface program when it becomes a reality unless the government develops ways for troops to object without consequence to using the technology.

“Limited personal autonomy among military personnel, as well as a lack of information about long-term health risks, have led some ethicists outside of government to argue that [brain-computer-interface or BCI] interventions, such as noninvasive brain stimulation techniques, are currently inappropriate for a military or security sector setting,” detailed a 2020 report from Rand, a nonprofit think tank that researches issues in the military.

The Rand researchers wrote that the military services should consider “arbitration mechanisms” or ways for troops to civilly discuss the concerns of orders “so that service members and their commanding officers may discuss or object to unethical or harmful uses of BCI technology.”

Gene Civillico, a neuroscientist who has prior stints at the Food and Drug Administration and the National Institutes of Health, told Military.com in an interview that the ethical questions of neurotechnology can be solved for the military pending the right regulatory and research processes, but there will always be an extra level of scrutiny paid to anything involving the brain.

And enhancement, rather than just curing ailments, raises further concerns.

“It’s hard to distinguish sometimes between what’s medical and what might be useful from a military mission standpoint,” Civillico said. “The FDA might approve a device to enhance memory, because it would be seen as a medical indication that this device alleviates memory loss that’s associated with Alzheimer’s or something else. But suppose that the military wanted to make it so that someone could remember more than they had ever been able to remember before?”

Service members could also find more than their memories altered by enhanced brain performance.

“There’s also this really complicated question of what do you do when you give somebody enhancing technology that becomes integral to their own self-identity,” Nita Farahany, a Duke University professor, futurist and author of “The Battle for Your Brain: Defending the Right to Think Freely in the Age of Neurotechnology,” told Military.com.

“Then they leave the military and they no longer can use that enhancing technology, which has become core to the way that they understand and interact with the rest of the world,” added Farahany, who served on then-President Barack Obama’s Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues and recently resigned from DARPA’s ethical, legal and social implications committee.

Shortly after laying his eyes on that young, wounded boy in Afghanistan two decades ago, Ling knew quickly that research into connecting the mind to machines would open up all kinds of possibilities for the brain.

He’s confident the military will keep ethics at the forefront of pioneering research, he said. But he can’t promise that America’s adversaries will do the same.

“You could change the human experience, and this little project that we did opens the possibility,” Ling said.

“You can’t put the genie back in the bottle.”

— Thomas Novelly can be reached at [email protected]. Follow him on Twitter @TomNovelly.

— Zachary Fryer-Biggs is the managing editor for news at Military.com. He can be reached at [email protected].

Related: After Terminator Arm, DARPA Wants Implantable Hard Drive for the Brain