Sara Lopez, 24, didn’t learn Spanish from her parents because they didn’t want her to go through the discrimination they faced for speaking the language back in the 1980s.

“Their teachers were mostly white and would punish my parents or other students for speaking Spanish,” Lopez, a Los Angeles resident, said.

For a while, Lopez felt embarrassed for not being able to understand or communicate in Spanish and was frequently teased and bullied for not “speaking Spanish right.”

Eventually, she said, her parents healed from their childhood experiences and started to encourage her to learn more Spanish. Lopez now takes pride in being a “no sabo kid” — and wants people to understand there are many others who’ve had a similar experience.

In recent years, the phrase “no sabo,” which is the incorrect way of saying “I don’t know” in Spanish (the correct translation is “no sé”) has become synonymous with young Latinos who aren’t fluent in Spanish.

But what used to be a put-down term has now become a cultural hit online and a widespread meme: TikTok alone has more than 644 million video views with the hashtag #nosabo and #nosabokid is close to 400 million.

On social media, teens and young adults will poke fun at no sabo experiences. In one TikTok video, a “no sabo” teen asks her sibling if she’s seen the “crayola” their mom is looking for, meaning carriola, or stroller. Another video shows a no sabo “olympics” where teens are quizzed on the correct Spanish word.

While most of the videos are playful and even hilarious, the growing trend of Latinos “clapping back” at the policing of Spanish has opened up an age-old debate on what it means to be Hispanic or Latino in the U.S.

Dr. David Hayes Bautista, professor and director at the UCLA Center for the Study of Latino Health and Culture, said he likes to remind people that being “Latino is separable from Spanish,” and that being Latino isn’t a monolith — some may speak Spanish, some may speak Indigenous dialects and some may only know English.

“There are about 63 million Latinos in the United States, and no two people are Latino in the same way. It’s not language that makes you Latino,” Bautista said.

The debate is relevant for a growing number of Americans: Currently, a quarter of U.S. children are Latino.

For more from NBC Latino, sign up for our weekly newsletter.

In 2021, over 7 in 10 Latinos aged 5 and up spoke English proficiently — an increase of 59% since 2000 — according to the Pew Research Center, while there’s been a decline in those who speak Spanish at home.

As the #nosabo kids say in their own words online, they still hold a connection to their Latino culture despite any language challenges.

It’s also resulted in Latinos who have decided to learn the language on their own terms in new and creative ways — and to take a look at how previous generations of Americans were discouraged from speaking Spanish, or even not allowed to.

When Spanish wasn’t allowed

To be on the receiving end of no sabo criticism can be intense, as Diosa Femme, 29, the co-host alongside Mala Muñoz of the podcast Locatora Radio, knows.

In late March, a clip of her speaking as a guest on a different podcast about how young Latinos are reclaiming the no sabo identity and how there’s been a violent history against speaking Spanish went viral. Femme was labeled a no sabo kid and became public enemy No. 1.

“Some of the comments that I got on the video were things like, ‘I don’t know where these girls are getting their information from. Why is everyone a victim? That’s stupid,’ like really discrediting what I was saying,” said Femme, who’s Peruvian Mexican and actually fluent in Spanish. She grew up in a strict Spanish-speaking household in Los Angeles.

The outrage is what motivated Femme and Muñoz to produce a two-part podcast episode on the issue to inform newer generations on the subject. “These are things that happened in the Southwest — I didn’t know that this was something that would be so contentious,” Femme told NBC News.

Most Americans don’t know California initially had a bilingual constitution — the region was formerly Mexican and Spanish. As Hispanics in the state Legislature began to lose political power, so did their right to speak Spanish publicly.

The U.S. has had a history of forcing Americans to speak English; this was the case with Native American boarding schools, for example.

“Mexican American children were put through similar violent language training,” Alexandro José Gradilla, an associate professor of Chicano/a studies at California State University, Fullerton, said. “They were physically hit and beat for speaking Spanish at school. … Teachers had the right to physically punish children.”

A notable example took place in Marfa, Texas, at the Blackwell School, which has since been turned into a national historic site.

Built as a segregated school for Mexican American and Mexican children in 1909, students were beaten with paddles and forced to speak only English on campus. In 1954, the school held a mock funeral ceremony and buried slips of paper with Spanish words written on them. The school closed in 1965.

Muñoz, 31, whose family comes from generations of farmworkers in California’s conservative Kern County, said her relatives struggled with passing down Spanish from generation to generation.

“I grew up just constantly hearing the reason dad speaks terrible Spanish is because he wasn’t allowed to speak Spanish. It was kept from him. They were being beaten at school. And that’s why he speaks his Spanglish, and that’s why we speak our hybridized Spanglish,” said Muñoz, who is Mexican American.

Femme said her mother’s name was changed by her elementary school teacher to “Maggie” from Margarita. Her older brother was placed in an English-only track in elementary school after a speech pathologist said he was struggling because he spoke Spanish at home, which was “detrimental.”

“Those examples are more common than we like to realize as a community because we, as Latinos, very much live in a culture of silence where we don’t talk about the things that we’ve experienced,” Femme said.

“What the no sabo discussion is ignoring is that longer history of our public schools, our public cultures are very English-oriented,” Gradilla said.

At the same time, generations of Latinos have been criticized for not speaking Spanish. Decades ago, the term pocho — like Chicano — was used as a derogatory term for Mexican Americans who were deemed “ni de aquí, ne de allá,” (not from here, not from there). Puerto Ricans born and raised in the U.S. were referred to as “nuyoricans” (since so many lived in New York) and criticized for not speaking Spanish like those on the island.

Becoming more fluent — without the shame

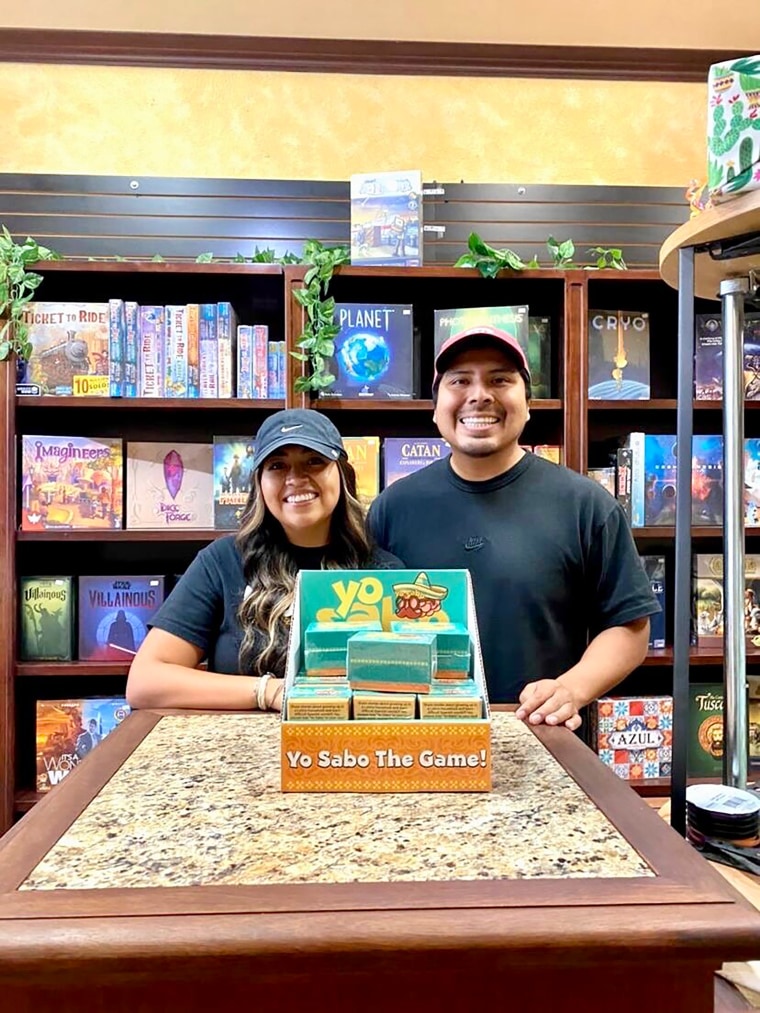

Carlos Torres, 31, and Jessica Rosales, 31, a Mexican American couple, both come from families who immigrated from Mexico. Their parents instilled in them that education and learning English were vital paths to success. And though their parents told them it was important to keep speaking Spanish, they didn’t find many opportunities to do so.

Torres and Rosales created a card game last April, “Yo Sabo,” as a way to remember some tricky Spanish words and help monolingual Latinos reconnect with their childhood.

The card game can be played in three ways: in the first version, a player gives the English word and another guesses the Spanish translation; a second focuses on Latino trivia about Latino customs and traditions; and a third version involves charades.

“Now looking back at our memories, it’s like, how do we help families now that had that challenge and didn’t have the opportunity to keep practicing?” Rosales said. “Now they have something fun to use.”

Wendy Ramirez, 46, and Jackie Rodriguez, 35, started Spanish Sin Pena (Spanish Without Shame), a program for those trying to become fluent in Spanish.

“I don’t think people realize that even when parents are intentional about keeping the language they already have, it is so difficult because we live in a place where English is spoken everywhere,” Ramirez said. “Some parents are just trying to get by and survive and they don’t have the time and space to make it a priority.”

Their program came from experience; Ramirez found herself struggling to keep up with Spanish speakers when she was studying in Mexico City.

Founded in 2018, Spanish Sin Pena has now grown to more than a thousand registered users per year, mostly Latinos who want to learn Spanish to connect more with their culture. Classes are offered at different levels depending on one’s fluency level.

Participants share stories, including tough conversations about their shame at not speaking Spanish and experiences with racism and colorism. But it’s also fun and not always serious — there are options to learn Spanish through cultural experiences like cooking classes, dance classes and cultural immersion trips to various countries.

“It’s difficult to have safe spaces like ours to ask questions and to not make it so heavy,” Rodriguez said. “Being able to see a whole community of people who share a story that sounds just like yours, that’s healing.”

Rodriguez has also been characterized as a no sabo kid but since starting Spanish Sin Pena, she now takes ownership of the term.

“I love Spanglish and I’m going to speak it for life and I’m not ashamed about that,” she said. “A language isn’t going to make me any less Latina. It’s in my blood. It’s in my hips. It’s in my sazón (seasoning) when I’m cooking.”

Veronica Benavides, 36, grew up in Houston and had trouble communicating with her grandmother who only spoke Spanish. In high school, she was shamed for not speaking fluent Spanish by her peers.

“My reaction was to reject it more — I felt a sense of disconnection there,” she said.

It wasn’t until college that she connected her experiences to history: Her parents didn’t teach her Spanish because they attended English-only schools in the Rio Grande Valley and were punished physically and verbally for speaking it.

Benavides went on to learn Spanish and referred to herself as a “sí sabo kid,” which helped her develop a greater relationship with her grandmother.

“I was like, ‘Whoa, this woman had this whole life that I didn’t know about. She had lovers. She had quarrels with her family; she had children that she had lost that I didn’t know about. … This whole family history, at least with me and my generation, could have been lost,” Benavides said.

In 2021, Benavides launched Bilingual Generation, which partners with schools and families to deliver programs that support bilingualism as a tool for academic success.

This academic year, she’s working with the school system she once attended as a kid in Aldine, a Houston suburb, to help bring dual language programming.

Torres, the “Yo Sabo” card game co-creator, said, that in the end, “Language is so fluid. It doesn’t matter how much you know or how little you know — we’re all in this really together, just learning. … We need to stop being our harshest critics.”