The Food and Drug Administration may be one step closer to what could be the first approval of a drug that uses the groundbreaking gene-editing tool CRISPR.

The drug, called exa-cel, treats sickle cell disease, an inherited blood disorder that affects an estimated 100,000 people in the U.S., most of whom are Black, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

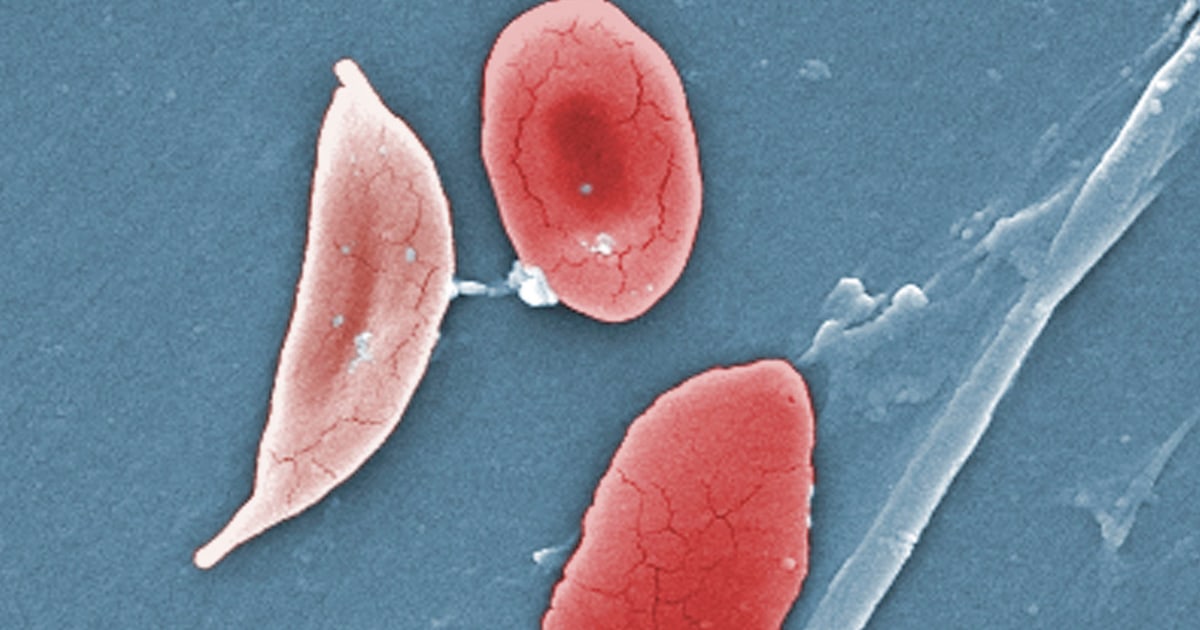

The illness causes the body’s red blood cells, usually disk-shaped, to take on a crescent or sickle shape. When that occurs, the cells can clump together, leading to clots and blockages in the blood vessels. That may result in a variety of complications, including excruciating pain, trouble breathing or stroke.

“The promise of a universally available, potentially curative option for individuals with sickle cell disease is revolutionary,” said Dr. Biree Andemariam, a hematologist and the director of the New England Sickle Cell Institute at the University of Connecticut. Andemariam has consulted for Vertex Pharmaceuticals, which makes exa-cel.

The illness is chronic, and the only known cure is a bone marrow transplant from a donor, which carries the risk of rejection.

The gene-editing drug, from Vertex along with CRISPR Therapeutics, would eliminate the need for a donor. Instead, it works by changing the DNA in the patient’s blood cells.

Exa-cel uses CRISPR, a gene-editing tool that’s able to target certain stretches of DNA and snip them out, essentially deleting the unwanted section that, in the case of sickle cell disease, causes the cells to take on a crescent shape.

On Tuesday, an FDA advisory committee reviewed the drug at an all-day meeting. Such advisory meetings are usually one of the final steps before the agency decides whether to approve a drug. The FDA is expected to issue a final ruling by Dec. 8.

No drug that uses CRISPR gene-editing — which was invented in 2009 — has been granted FDA approval. What’s more, Tuesday’s meeting looked different from past advisory committee meetings. In this case, the panel was not asked to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of Vertex’s drug, which is seeking approval for people ages 12 and up with severe illness.

Instead, the focus was on the “off-target” effects of CRISPR — that is, when the technology makes cuts to other stretches of the DNA other than the intended target — and how the FDA should think about those risks moving forward.

It’s unclear what effects an off-target edit would have on a patient — it depends entirely on where it happens in the DNA.

“Off-target editing does not necessarily mean that there’s going to be a bad outcome,” said committee member Scot Wolfe, a professor of molecular, cell and cancer biology at UMass Chan Medical School.

“There seems to be a lot of uncertainty, a lot of unknowns, about what these off-target changes might mean,” said committee member Lisa Lee, an epidemiologist and the director of scholarly integrity and research compliance at Virginia Tech.

“Are those unknowns more harmful than not allowing this to go forward?” Lee asked.

Vertex Pharmaceuticals presented research findings on 46 people who received the treatment. Among the 30 patients with a minimum of 18 months of follow-up, 29 no longer experienced severe pain crises.

The company said there was no evidence of “off-target” effects from the therapy, but committee members questioned whether Vertex’s analysis was thorough enough.

“I’m not questioning that this product is important for our patients,” said a committee member, Dr. Joseph Wu, the director of the Stanford Cardiovascular Institute. “I’m just saying we’re at a point in which this thing is going to take off and wouldn’t it be nice to have more additional data.”

A big step forward but not a simple cure

Vertex has not disclosed the price of gene therapy, but, if it is approved, it is expected to be extremely expensive, potentially costing as much as $2 million per patient, according to a report from the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, a nonprofit group that helps determine fair prices for drugs.

Dr. Stephan Grupp, the chief of the therapy and transplant section of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, who consults for Vertex, said in an email that if it is approved, the step next would be to make sure patients can get access.

“I do think that there’re going to have to be a lot of questions answered regarding access,” Andemariam said.

While exa-cel is technically a one-time treatment, the process involves a number of steps.

It starts by extracting stem cells from the patient’s blood. The stem cells are edited with exa-cel in the lab to delete the snippet of DNA that causes the cells to warp. Before the cells can be reinfused back into the patient, however, the patient must undergo chemotherapy to kill off cells that produce the sickle-shaped cells.

Follow NBC HEALTH on Twitter & Facebook.