Four years after it bought Mission Hospital, an 815-bed facility in Asheville, North Carolina, HCA Healthcare is under fire in the region, threatened with a lawsuit by the state attorney general and facing criticism from nurses and at least 124 current and former Mission doctors who say HCA, the nation’s largest for-profit hospital chain, is imperiling patient care at the facility in its pursuit of profits.

“Profits over people is not an ethic, model, or aspiration that can deliver the quality of care we all expect and deserve,” the doctors wrote in a letter to the independent monitor watching over management of the hospital. “We ask that hospital leadership look at economics as if people mattered.”

On Oct. 31, the office of North Carolina Attorney General Josh Stein wrote a letter to a foundation called Dogwood Health Trust, contending that HCA had violated the terms of the agreement it struck in 2019 when it bought Mission, a formerly nonprofit facility. Under that agreement, HCA had promised to continue providing an array of specific services for a decade at the hospital, including those involving behavioral health, emergency and trauma, oncology and pediatrics. Dogwood Health Trust was created when HCA bought Mission and works to improve the health of people in Western North Carolina.

The attorney general’s office noted a breach of that agreement at Mission, citing diminished care in the hospital’s oncology unit and its emergency department. The letter warned that if HCA does not cure the violations within 40 days, Stein “is authorized to file suit.”

A Mission spokeswoman said in a statement that the hospital is proud of the health care it provides and is disappointed by the attorney general’s statements. “We continue to meet, and often exceed, the obligations under the asset purchase agreement,” she said. “The independent monitor has confirmed compliance every year since the agreement was signed in 2019.” The spokeswoman also provided a letter signed by 75 Mission practitioners who say patients continue to receive great care at the facility.

Dr. Martin Palmeri, an oncologist who practiced at Mission before HCA took over and has continued to practice there, has a different view. Before the HCA buyout, he said in an interview with NBC News, local oncologists had developed excellent clinical programs to treat patients in the region. But after HCA acquired Mission, he said, nursing staff declined precipitously, the number of chemotherapy-trained pharmacists went from four to one, and the HCA labs services and turnaround times declined significantly. These deficiencies made it difficult to treat the full array of cancer patients coming to the hospital, he said.

After years of trying unsuccessfully to resolve these problems, Palmeri said the only choice he and his colleagues had was to stop offering three oncology services at which he said Mission had previously excelled. They were treatments for acute myelogenous leukemia, acute lymphocytic leukemia and primary central nervous system lymphoma. “We felt it would be best for our patients to get their complex hematology care somewhere else,” he said.

HCA declined to address Palmeri’s criticisms. But a spokesman provided letters the company has sent to North Carolina officials disputing criticisms of its oncology services. The letters call them “unfounded” and say HCA’s takeover of Mission has resulted in “enhanced oncology services” there. Moreover, nurse-to-patient ratios in oncology are “flexible and adaptable to patient needs” and consistent with best practices at HCA’s cancer institute, the letters say.

Regarding understaffing of chemo-trained pharmacists, HCA told state officials in the letters that it is “continuing to pursue opportunities to further enhance its pharmacy coverage and offerings.” As for the lab problems, HCA said, “Mission is enhancing lab technician training to permit technician staffing that better targets volume needs on a day-to-day basis, which will further reduce processing times.”

Mission’s emergency department is another problem, according to doctors, nurses and patients. Bryan Robinson, a psychotherapist and professor emeritus at the University of North Carolina, said he has experienced the deficiencies first-hand. In 2019, before HCA took over the hospital, Robinson told NBC News he visited Mission’s emergency department with chest pains. He did not have to wait, quickly received a stent and departed.

In late September, when he returned to Mission’s emergency department with a low heart rate, he had a vastly different experience. After waiting for six hours, Robinson, 78, said he was called to a partitioned area where his diagnosis was discussed. It was neither private nor soundproof, he said, adding that he could hear about other patients’ conditions as he felt sure they heard about his. He feels the hospital violated his privacy rights under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, known as HIPAA. He complained to Mission but did not get a response, he said.

“The worst part of all this is the doctors and nurses are phenomenal — this is not about them,” Robinson said. “It’s about this facility that has been turned into Kentucky Fried Hospital.”

Mission’s spokeswoman declined to comment on Robinson’s points. The hospital’s chief executive, Chad Patrick, declined NBC News’ request for an interview.

HCA Healthcare operates almost 180 hospitals in the U.S. and generates billions in earnings. NBC News has reported extensively on HCA this year, examining company practices that more than 60 doctors and nurses say put profits ahead of patients. Among those reports was one in January on understaffing at HCA facilities, centering on Mission Hospital. Developments in the HCA Mission dispute have been covered closely by Asheville Watchdog, a free, local and not-for-profit news organization.

On Nov. 1, EMS in nearby McDowell County, North Carolina, stopped transferring nonemergency patients to Mission Hospital, citing hourslong wait times for paramedics who must continue caring for their patients until they are admitted.

“Our agency has worked with HCA for more than a year now to address and improve the extended wait times at Mission Hospital,” Will Kehler, emergency services director for McDowell County, said in a press release. “Unfortunately, we are making no progress and the situation is getting worse. Paramedics waiting 1-2 hours in the ER for a bed and a nurse to assume care is a situation that should never be deemed acceptable.”

The Mission spokeswoman did not respond to a request for comment on the McDowell County EMS’s action.

The 124 doctors who signed the letter criticizing HCA’s management of Mission included nine former chiefs of staff at the hospital, six former Mission board members, and 66 actively practicing physicians, including 17 who signed themselves as “anonymous,” according to a former Mission doctor.

Several current and former Mission doctors who spoke with NBC News did so on the condition of anonymity because they fear retaliation by HCA. Noting that more than 200 doctors have left the hospital since HCA took over, the letter said: “Stifling the ability to speak freely undercuts the communication necessary for shared trust, continued improvement, and a greater good.”

The letter supporting Mission management signed by 75 practitioners at the hospital said care continues to be excellent. “There was turnover within both the hospital and physician leadership which meant new relationships had to be formed,” the letter said. “This, no doubt, was emotionally difficult and has taken time for us to heal.”

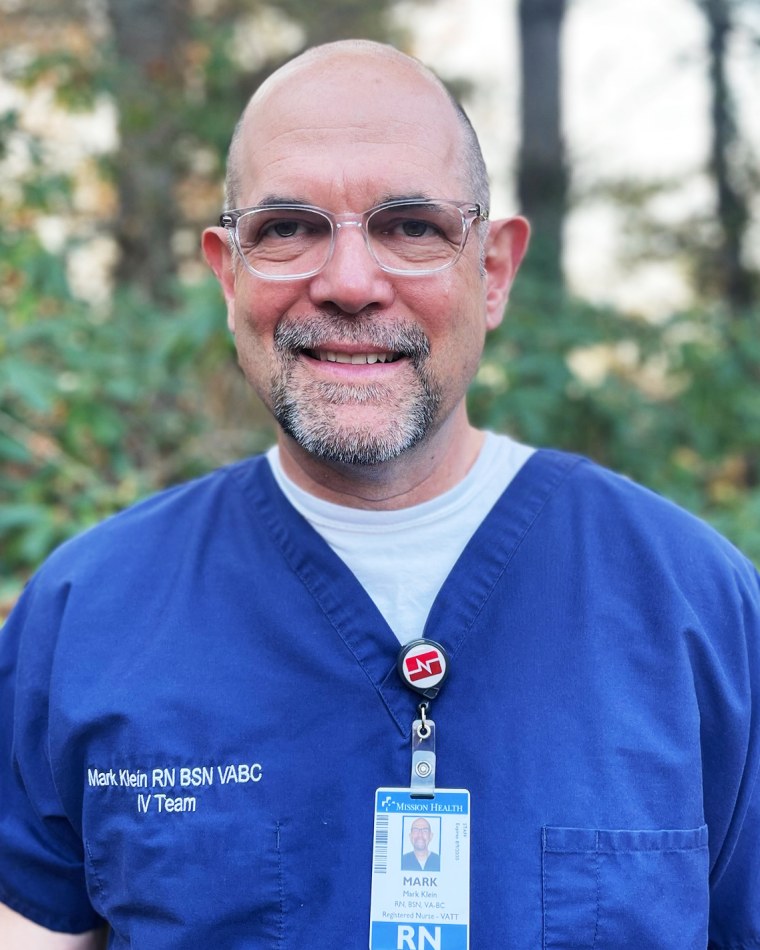

Two longtime Mission nurses spoke with NBC News for this article — Kelly Coward, a cardiac ICU nurse and Mark Klein, a vascular access nurse. After HCA acquired Mission, its nursing staff voted to unionize.

Both Coward and Klein worked at Mission before the HCA takeover and still work there, and they discussed the differences. Most center on understaffing that threatens patients at the facility, they said. For example, each ICU nurse now often cares for three patients, they say, not one or two, as is safe; and charge nurses now have patients they must care for, which was not the case previously. Unit secretaries are gone, both nurses said, so there’s no one to answer phones, and the number of nursing assistants has dwindled. As a result, nurses must pick up those duties, Coward and Klein said.

In the emergency department, Klein said, “the triage area was never a treatment area before; now it is. The diminishment is across the board — HCA may be continuing services, but they’re not continuing them at the same level.”

Coward described two important services for cardiac patients that vanished under HCA. One, called Heart Path, was an educational program that helped new heart patients understand their diagnoses. “The team of nurses told them what to expect,” she said, “made sure they had their follow-up appointments and all the tools they needed to be successful with their new diagnosis.” Under another program that disappeared under HCA, a nurse would follow patients recently diagnosed with heart disease through hospital discharge and subsequent appointments with physicians.

“These people are going to slip through the cracks,” Coward said.

The Mission spokeswoman declined to comment on the nurses’ criticisms.

Scrutiny on HCA’s stewardship of Mission coincides with a growing call from some physician groups to ban corporations practicing medicine, which they say imperils both patients and doctors. Over 30 states in the nation have laws barring corporations from practicing medicine to prevent health care from being tainted by commercial influences and the drive for profits. California, for example, prohibits corporations or other nonlicensed people or entities from practicing medicine, assisting in the unlicensed practice of medicine, employing physicians or owning physician practices.

But few states enforce these laws and the corporate ownership of physician practices and other health care entities has grown significantly in recent years. “Profit-oriented corporations are exerting control over physicians and the practice of medicine throughout the country,” said Dr. Mitchell Li, a practicing emergency physician and founder of Take Medicine Back, a public benefit company pushing for a bar on corporations practicing medicine. “But there are few places where this is more pronounced than in Western North Carolina where HCA took over Mission. The company has joined forces with Wall Street private-equity firms that employ physicians to extract wealth from the community and those physicians can be ‘removed from the schedule’ on a whim without justification. If they cross HCA administration, they have few alternative opportunities for work.”

The Mission spokeswoman did not respond to a request for comment on Li’s statement.

In Florida, where HCA operates 46 hospitals, two state lawmakers have drafted a bill to be submitted in the January legislative session that would bar entities other than physician groups, not-for-profit hospitals and medical schools from employing, controlling or interfering with a physician’s clinical judgment.

Kelly Skidmore, a Democrat in the Florida House representing a part of Palm Beach County, is one of the bill’s proponents. “Seventy-four percent of Florida physicians are under corporate ownership,” Skidmore told NBC News. “The practice of medicine has been stolen from physicians and I want to give it back to them.”

She acknowledges a long fight ahead.