Deaths due to cardiac arrest in college athletes have been steadily declining over the last 20 years, a new study finds.

An analysis of data from more than 2 million NCAA athletes revealed that 143 had died after a cardiac arrest that occurred while they were playing their sport and that there was wide variation in the risk of death after a sudden heart stoppage, depending on the player’s race, gender and sport, according to the research presented Monday at the annual meeting of the American Heart Association .

“We don’t know why the rate of cardiac arrest deaths has been going down,” said study co-author Dr. Kimberly Harmon, a professor in the departments of family medicine and orthopedics and sports medicine at the University of Washington in Seattle.

“You could hypothesize that it’s because there are better emergency action plans when there is a cardiac arrest, more people who know CPR and clear access to a defibrillator,” she said. “When someone passes out suddenly, you should think cardiac arrest until evidence shows otherwise.”

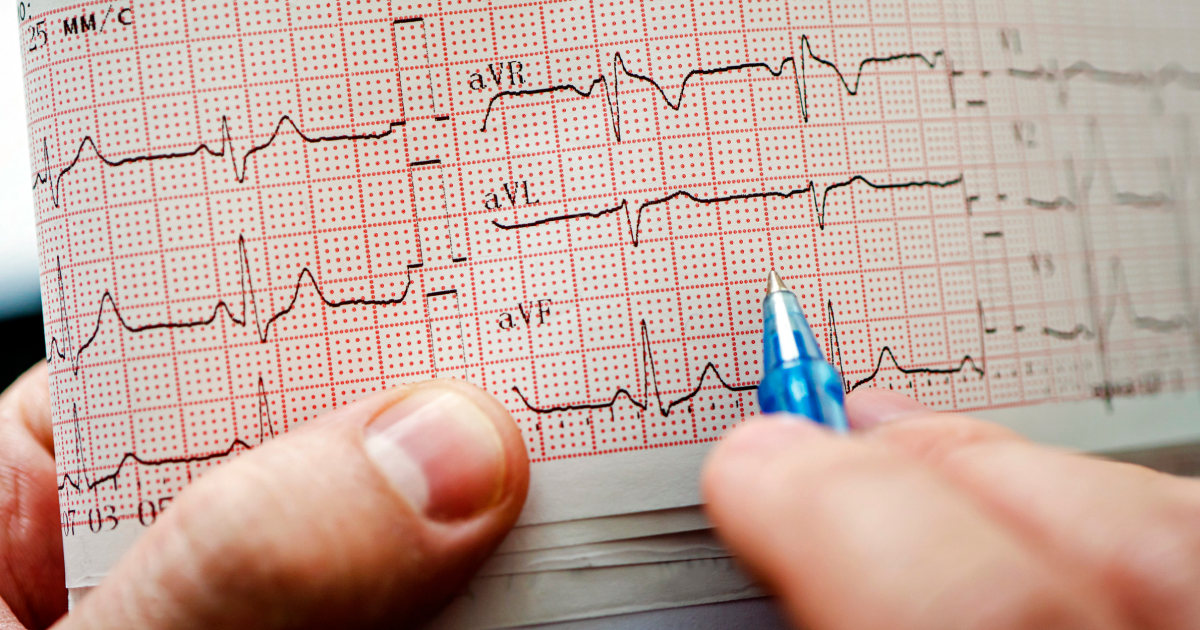

The decrease could also be due to more screening, with colleges increasingly requiring athletes be cleared to play with an exam that includes an electrocardiogram (EKG or ECG), which measures the heart’s electrical activity and can detect dangerous heart rhythms.

“The patterns on an EKG can also tell a lot about the shape and size of the heart,” Harmon said. “In athletes, we are primarily looking for electrical or heart muscle disease.”

It’s been shown that screening that includes an EKG will catch between two-thirds and three-quarters of athletes at risk, she said.

Athletes who have an abnormal EKG might be sent for an echocardiogram, an ultrasound of the organ.

Cardiac arrest in college athletes is relatively rare: In any given year, 1 in 63,000 college athletes die from cardiac arrest, the study found. Harmon’s data showed that in any given year, there were eight sudden cardiac deaths in NCAA athletes.

However, when the researchers dug down into the data by gender, race and sport, they found that there were some very striking differences.

Basketball players had a higher risk, at 1 in 8,188 in any given years.

“If you consider athletes who played four years, then it’s 1 in a little over 2,000,” Harmon said.

Men were at higher risk than women: 1 in 43,348, compared to 1 in 164,504 women college athletes in any given year.

Deaths among Black athletes were three times more common than those among white players: 1 in 27,217, compared to 1 in 74,581 in any given year. Sport cardiologists have previously suggested the reasons that Black athletes face greater risk of cardiac arrest could include genetics, lifestyle and which sport they play.

What causes cardiac arrest in athletes?

Autopsies found no heart defects in the majority of those who died. Most likely in these cases, there was an electrical short circuit, Harmon said.

“When electrical activity in the heart is not coordinated, it quivers and does not pump blood and the person passes out,” she added.

The study didn’t look at how many athletes had a cardiac arrest and survived, something researchers hope to explore in the future.

What’s striking about the study is that even though the incidence of sudden cardiac death is low overall, in certain populations, it’s less rare, said Dr. Mary Ann McLaughlin, director of cardiovascular wellness at the Mount Sinai Fuster Heart Hospital in New York City.

McLaughlin was surprised by how high the rate of sudden cardiac death in basketball players was and speculated that it might be due to stresses on the heart as players sprinted up and down the court.

Should all high school and college athletes be screened before being allowed on sports teams?

It’s complicated, experts said, because some athletes and their families might not have the ability to pay for physicals, especially those that include an EKG.

“We don’t think it should be a barrier to participation because being on a team has so many physical and emotional benefits,” Harmon said.

The new study underscores the importance of schools having an easily accessible defibrillator — which can jolt the heart back to beating — and a team trained to deal with cardiac arrests, said Dr. English Flack, an associate professor of pediatric cardiology at the Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at the Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

It was also “pretty reassuring to see that the incidence of sudden cardiac death has decreased,” she said. “The next reasonable question is, why and how. Either the rate of cardiac arrest stayed the same and the number of athletes who were rescued increased or the rate of cardiac arrest is decreasing due to increased screening.”

The focus should be on making sure every school has an automatic electronic defibrillator and a team that can help resuscitate an athlete who experiences a cardiac arrest, Flack said

“Many schools can’t afford an AED,” she said.

McLaughlin would also like to see screening rates increase: “The risks associated with doing a physical exam and EKG are very low compared to the potential benefit of saving a life in someone who has a risk for sudden death.”