Could kids still be eating contaminated WanaBana cinnamon applesauce pouches?

Millions of the pouches have been recalled since late October. It’s unclear how many of those pouches were sold or, if they were sold, whether they were returned or disposed of, but the Food and Drug Administration says they have a shelf life of 14 months.

That means for parents unaware of the recall, it’s possible that the applesauce pouches could still be in kitchen cabinets.

“Although this is a very specific type of product, what families will often do is a child will like a particular flavor of a product, and parents, looking for convenience and making sure their kids are getting lots of nutrition, will really go all in,” said Dr. Scott Hadland, a pediatrician at Mass General Hospital for Children in Boston. “So the risk to a child can be really high if they keep consuming these and if their parents are unaware of the recall.”

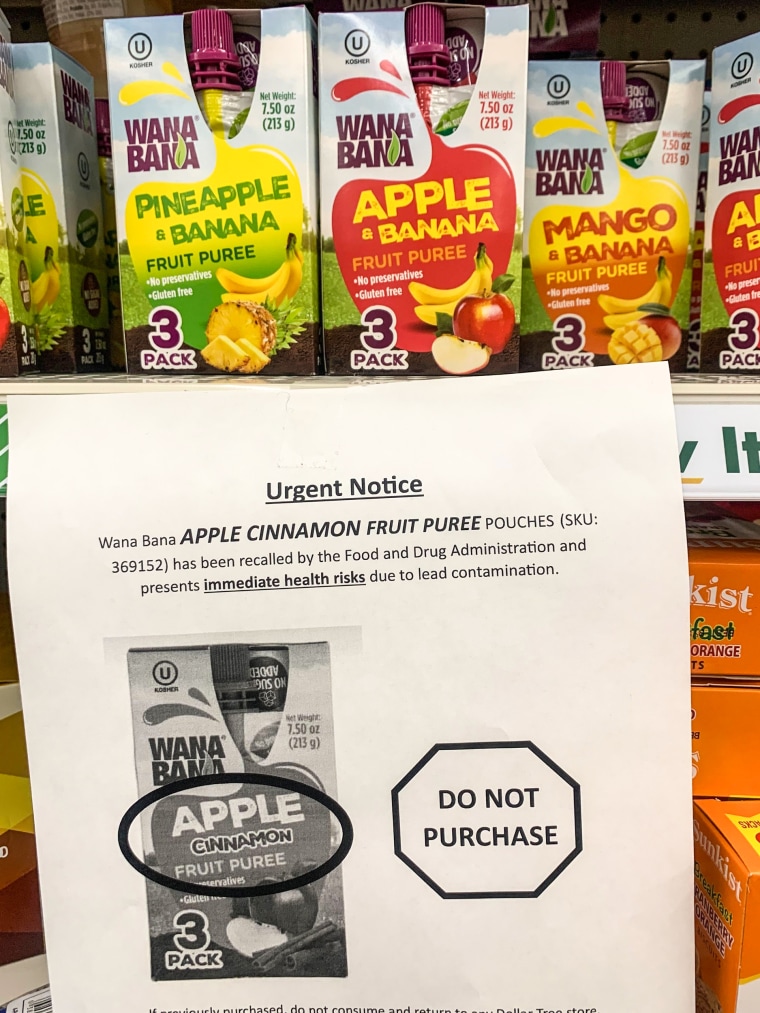

The FDA said Tuesday that it was looking into a report that the recalled WanaBana apple cinnamon fruit puree could still be found on store shelves at some Family Dollar-Dollar Tree combination locations. The agency did not specify the source of the report, nor did it identify which particular stores might still have the contaminated pouches in stock.

An FDA spokesperson directed NBC News to Dollar Tree for a response, saying it does not have that information. A spokesperson for Dollar Tree did not respond to several requests for comment.

This is not the first time since the recall that the FDA has said it was aware that the recalled product could still be found on some Dollar Tree shelves. It said that as of last week, three-packs of the WanaBana cinnamon applesauce pouches were “still on the shelves at several Dollar Tree stores in multiple states.”

The FDA issued a similar statement on Nov. 22. Dollar Tree said in a statement at the time that it was “working with store operations teams to ensure the recalled WanaBana Apple Cinnamon Fruit Puree pouches are no longer in stores and destroyed according to FDA guidelines” and that the stores’ registers were programmed not to allow sales of the recalled product to go through.

As of Friday, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had received 205 reports of elevated blood lead levels linked to the cinnamon applesauce pouches across 33 states. Sixty-seven of those reports have been confirmed, the CDC said, using blood tests within three months of the applesauce’s having been eaten and after other sources of lead exposure were ruled out. Another 122 of the cases are probable, meaning another source of exposure has not been ruled out, and 16 cases are suspected, which need more testing.

Hadland said there most likely are more cases — lead exposure may not cause symptoms, and families will find out about elevated blood lead levels only through blood tests, potentially delaying case counts.

In addition to the WanaBana apple cinnamon fruit puree, two other products were also recalled: Schnucks applesauce pouches with cinnamon and Weis cinnamon applesauce. Both are made by WanaBana USA.

WanaBana did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

WanaBana said in a news release Monday that it continues to work with the FDA in its investigation. It also said it would reimburse parents of children affected by the recall up to a total of $150 for health care visits and blood lead tests related to the product.

What can parents do?

Children under 6 are the most vulnerable to lead poisoning, the CDC says. Lead exposure can lead to damage to the nervous system and brain, lower IQ and underperformance in school. It can also cause problems with learning, behavior, hearing and speech, the agency says.

Some children may experience headaches and ongoing gastrointestinal symptoms, including stomach pain, nausea, vomiting and constipation, from lead exposure, Hadland said.

“It tends to be progressive and last for a long time rather than coming and going, like if a child has a stomach bug,” he said.

But often, children show no immediate signs of lead poisoning.

Dr. Adam Keating, a primary care pediatrician at the Cleveland Clinic, recommended parents follow routine screening guidelines to catch lead exposure in children.

Currently, the CDC recommends that all children get blood tests for lead exposure at ages 1 and 2.

After the tests, pediatricians will often provide parents of 3- to 5-year-olds with a questionnaire to help determine whether there are any other known exposures that may require ongoing blood screening, Keating said.

Hadland said that if parents are concerned about a product their child has consumed, even if the child has had a previous blood lead test, they should consult a pediatrician immediately.

Laurie Beyranevand, the director of the Center for Agriculture and Food Systems at Vermont Law and Graduate School, said parents “should definitely” throw out the product if they find it in their cabinets.