Jennifer Benton’s daughter was just 5 years old when her kindergarten teacher pointed out something unusual: the young girl was developing breasts.

“It was really alarming,” said Benton, 39. “She may have been a tall little girl, but she was still a little girl.”

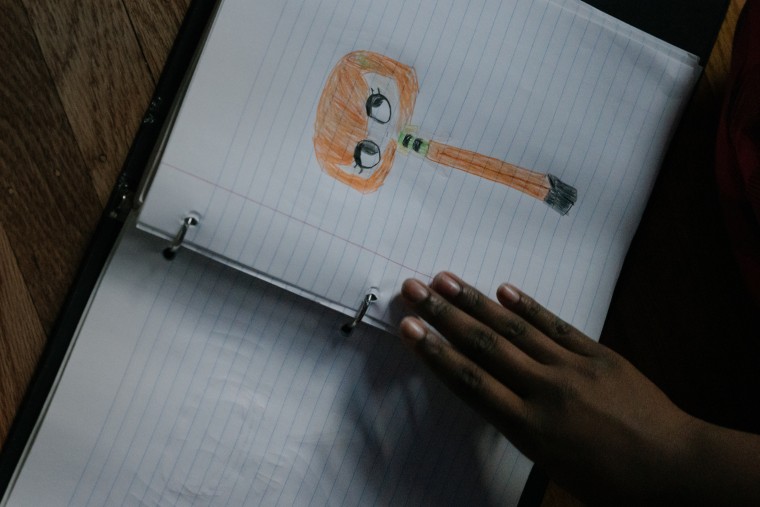

It was 2019 and the little girl loved playing with dolls, going out for ice cream, and watching her favorite Nick Jr. cartoon, “Bubble Guppies.”

“How is her body older than her actual age?” Benton remembers asking. At the teacher’s suggestion, Benton took the girl to see her local doctor in Ashtabula, Ohio.

At the time, Benton had never heard of precocious puberty. Having grown up in the Black community, where early puberty rates are among the highest in the U.S., Benton had known 7- and 8-year-old girls who’d had their periods or needed bras. But nobody in Benton’s family realized there was an actual medical diagnosis, or that prescription hormone treatments called puberty blockers could help slow the physical changes, if needed.

“Girls were just called ‘fast’ or ‘too mature for their age,’” Benton said. “I now understand they were struggling with precocious puberty.”

With puberty beginning at younger ages, especially among young Black girls, doctors say there’s an urgent need for greater awareness and education among families who may face hurdles in access to diagnosis and medical care.

In a 2022 article in the journal Pediatrics, researchers warned that biases in early puberty care had tremendous implications for the physical and emotional health of Black children.

“Although … race-based medicine is faulty and detrimental, its eradication from everyday practice remains a challenge,” pediatricians from the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University wrote.

How young is too young for puberty?

The average age of puberty’s onset — ranging from ages 8 to 13 for girls in the U.S. — has been dropping by about three months every decade over the last 40 years, according to a 2020 analysis of global data.

More concerning is that a growing number of children are showing signs of puberty — developing breasts, acne, pubic hair or a deepening of the voice — even younger than the average. Starting puberty significantly younger than age 8 for girls or age 9 for boys — a condition called precocious puberty — may have lasting repercussions on a child’s mental and physical development.

Precocious puberty is still rare, affecting fewer than 1% of the U.S. population, according to the National Institutes of Health. It’s unclear why it’s happening more, although possible causes include diet, obesity, genetics, socioeconomic status and potential exposure to certain chemicals.

Kids entering puberty earlier than the average can be mistakenly treated as older and inappropriately sexualized by society. Studies suggest early puberty may be linked to depression and anxiety. It may also increase the likelihood of developing eating disorders. Surprisingly, it can also keep children from growing to their full height because growth plates normally close toward the end of puberty.

“Sometimes when kids go through puberty early, their bone age advances very quickly,” said Dr. Aviva Sopher, an associate professor of pediatrics at the Columbia University Irving Medical Center.

Evidence shows that race and ethnicity have clear associations with early puberty. In 1997, a sweeping analysis published in the journal Pediatrics found 14.3% of Black girls had started developing breasts or pubic hair by age 6, compared to only 3.7% of 6-year-old white girls. More recently, a study published in the Journal of Adolescent Health earlier this year found Black girls were more than twice as likely to start puberty early than white girls. Hispanic girls were 1.16 times more likely to show signs of early puberty than white girls.

It’s difficult to know how many young Black and Hispanic children go through precocious puberty without medical guidance or treatment compared to white children. Even so, Dr. Karen Klein, a pediatric endocrinologist at Rady Hospital in San Diego, said medical care for precocious puberty remains unequal.

“There are definitely access-to-care issues,” she said.

Precocious puberty on the rise

In the mid-19th century, girls had their first periods — which typically come about two years after they begin to show signs of breasts or pubic hair — at age 16.5, on average.

Today, puberty begins between ages 8 and 13, on average, with girls typically having their first periods at age 12.4.

Italian researchers recently reported a sharp rise in the rates of rapidly progressive precocious puberty in girls during pandemic lockdowns. Similar trends were reported in Korea, Turkey and parts of China. A smaller study from New York City, published in the Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism, suggested Covid-related stress, inactivity and weight gain could be contributing to sharp spikes.

“It’s hard to prove this was the cause, but clearly there’s been an uptick,” said Dr. Roopa Kanakatti Shankar, a pediatric endocrinologist at Children’s National Hospital in Washington, D.C.

Boys, who typically begin puberty between 9 and 14, are also starting puberty earlier than in the past, but precocious puberty is much less common for young boys than girls. When a boy starts puberty far earlier than the normal range, it is often rooted in a serious cause like a brain tumor on the gland that produces hormones.

For girls, precocious puberty often lacks a clear cause, Sopher, the Columbia University pediatrician, said.

Doctors are emphatic that not all children need medical help, although they and their parents can benefit from awareness and guidance on what’s happening with their bodies. Determining the best course of treatment for an individual child can hinge on pediatricians taking the physical changes seriously, as well as access to specialists and complex, expensive tests.

Signs dismissed as ‘baby fat’

When Benton first brought her 5-year-old daughter Olivia to the pediatrician, the doctor dismissed the changes in her body as “baby fat.”

Even when Benton mentioned the had also been crying far more than usual, the doctor insisted she had little to worry about.

Later, once a specialist had diagnosed the child with precocious puberty, Benton said she wrote to Ohio’s medical board to complain about the missed diagnosis. She then discovered there had been no mention of “precocious puberty” in her daughter’s medical charts or visit notes at all, even after Benton had asked about it multiple times.

Some doctors previously suggested the diagnosis age for early puberty should be earlier for Black girls than for white girls. Shankar countered that precocious puberty diagnosis and treatment decisions shouldn’t be determined by race, or even age exclusively, but based on careful hormonal, physical and psychological tests.

“Just because they belong to a certain race and ethnicity, doesn’t mean they don’t still deserve a full, individualized assessment of whether they would benefit from treatment,” Shankar said.

However, doctors should be mindful not to “overmedicalize,” she said. Beyond physical tests and scans, pediatricians should take the time to get to know each child’s personality and circumstances to weigh who might benefit more from reassurance about the changes in their bodies rather than prescribing puberty blockers, which limit the production of sex hormones in the brain.

Although the injection drugs are shown to be safe for children with precocious puberty, they may cause rare side effects like the risk of reactions at the injection site or weakened bones if given to kids who don’t really need them.

“We have to tread a fine line,” Shankar said.

When are puberty blockers needed?

Considerable effort goes into deciding whether children under age 8 who are showing symptoms might benefit from the injectable hormone treatments, pediatric experts say.

For example, if a young girl starts growing breasts when she’s as young as 5 or 6, but then that growth slows down, she might not start to see other puberty-related changes until closer to the typical age range of 8 to 12 and still have her first period at a “normal” age.

For these girls, precocious puberty can be less concerning and puberty blockers may not be warranted.

“It depends on age, how rapidly progressive it is, how height might be affected, the maturity of the child, and how the family feels about things,” Sopher said.

A 2021 study published in the Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology estimated that 44 % of girls who started developing breasts between ages 7 and 8 had rapidly progressive precocious puberty; about 15 % required treatment.

“Those younger than 7 years old are more likely to need treatment in the majority of cases,” Shankar said.

Olivia had an X-ray to determine if her bones were growing faster than normal, an ultrasound to assess her ovaries and a series of blood tests to evaluate her hormone levels. Her results were all above normal for her age.

She went through a four-hour test during which she had her blood drawn, received a hormone shot to stimulate her pituitary gland, and then underwent additional blood draws to measure how her body’s hormone levels reacted.

By this point, it was 2020, and her pediatric endocrinologist said the girl, then 6, was on track to have her period by age 7, given how quickly her puberty was progressing.

Benton chose to start her on a puberty blocker called Lupron (leuprolide). The girl Jennifer Benton holds her daughter outside their home in Brookhaven, Pa., on Dec. 16, 2023.first got the shot once a month, then every three months for three years until she turned 9.

Long waits, high cost of care

A big hurdle for some families is the small number of pediatric endocrinologists who diagnose and treat precocious puberty. Many children and their families confront long waits for an appointment and must travel long distances.

“In many circumstances, access to care for precocious puberty has the same issue that we have with access to health care in general,” Shankar said. “Many of these children may not get care in a timely manner.”

In Benton’s case, she had to drive an hour to a Cleveland testing location and, after a three-month wait for an appointment, 45 minutes for each visit with a pediatric endocrinologist.

Insurance providers do typically pay for the drugs when there’s a clear diagnosis, experts say. Without insurance, prescription hormones — GnRH agonists that interrupt the pituitary gland’s production of sex hormones — may cost thousands per month.

According to the most recent U.S. census data, rates of uninsured children were twice as high among both Black and Hispanic populations than among non-Hispanic white children.

“For some families, cost can be a big deal, especially when copays are high,” Shankar said.

Most companies selling puberty blockers do offer copay assistance programs to help families afford the drugs, but applying for these programs can be a complicated process.

Once her daughter completed the required tests, Benton said, insurance covered her Lupron shots.

The power of a diagnosis

Patra Rhodes-Wilson’s daughter Sydney also started developing breast tissue at age 5. Like Benton, Rhodes-Wilson, who is Black, said she’d never heard of precocious puberty.

Sydney was diagnosed at age 7, but her hormone levels stabilized naturally when she was closer to 9.

Rhodes-Wilson, who lives in Champaign, Illinois, said her daughter benefited greatly from her precocious puberty diagnosis.

“There’s a sense of relief that this thing had a real name for it,” Rhodes-Wilson, 38, said. “I’m not making it up.”

At the guidance of Sydney’s doctor, Rhodes-Wilson started paying closer attention to the types of food she kept around the house and helped the girl stay active. Rhodes-Wilson believes the lifestyle changes helped keep Sydney’s hormone levels from continuing their sharp rise.

As for her daughter, Benton believes puberty blockers gave the girl her childhood back.

“She’s a smart girl, but she’s still learning and growing,” Benton said. “I didn’t want anyone thinking she should be wiser than what she is.”

Many doctors share the concern that very young girls could be treated as older because of their changing physical appearance.

“I’m even more protective of her now,” Rhodes-Wilson said of her daughter.

Following their daughters’ experiences, both Benton and Rhodes-Wilson say they’ve heard from friends, family and strangers on social media — most of them Black or Hispanic — who believe they’ve also gone through precocious puberty, or have children in its midst. Most had never heard of the condition or its treatment options, either.

“African-Americans don’t feel like we have any other resources, so we just kind of suck it up,” Rhodes-Wilson said. “I’m telling people now, ‘If something isn’t right with your child and your doctors do not take it serious, find a new doctor. Keep trying to get the help you need.’”