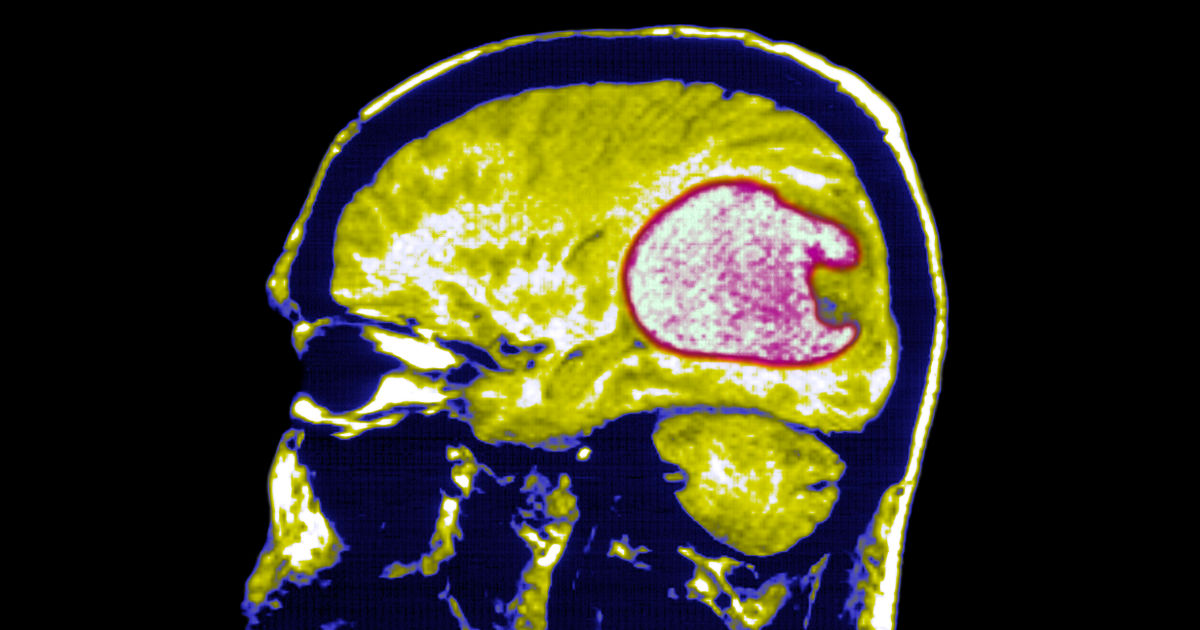

Two early trials published Wednesday showed promise in treating one of the deadliest types of cancer, glioblastoma.

The aggressive brain cancer, which took the lives of John McCain and Beau Biden, is only diagnosed at stage 4, and the five-year survival rate is around 10%.

The disease has no cure and, according to Dr. Michael Vogelbaum, chief of neurosurgery and program leader of neuro-oncology at Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, Florida, there have been no new drug approvals in the past two decades that have extended the lives of patients with glioblastoma.

The two clinical trials published Wednesday were extremely small, conducted on just nine patients in total, and much more research is needed, with larger trials, to determine how effective the therapy might be in the long run.

“All of these results are preliminary but encouraging,” said Vogelbaum, who wasn’t involved with either trial.

In the two unrelated trials, a novel take on an existing treatment for blood cancer was shown to be safe and it shrank tumors –– at least temporarily.

Both studies looked at the effects of a personalized immunotherapy called chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy — CAR-T therapy for short — in patients whose glioblastoma had returned after their initial treatment.

CAR-T therapy involves harvesting a person’s own immune cells and modifying them in a lab to seek out specific tumor proteins. The cells are then reintroduced into the body where they replicate, creating a surge of cancer-fighting immune cells.

The treatment is highly effective for certain blood cancers, but scientists are still studying whether modified versions of CAR-T therapy can be used for solid tumors like glioblastoma. These tumors, which account for the majority of cancers, present challenges that blood cancers do not.

Many blood cancers are homogeneous, meaning their cells are uniform. This gives CAR-T therapy a clear target to latch onto and attack. But solid tumors tend to have a variety of different cell types that can differ within individual tumors. This is particularly true for glioblastoma, which contains a large number of abnormal-looking cells.

“We had previous experience using a regular CAR in brain tumors but it wasn’t enough,” said Dr. Marcela Maus, director of the Cellular Immunotherapy Program at the Massachusetts General Cancer Center in Boston. Maus led one of the new studies, the results of which were published in The New England Journal of Medicine.

The original studies testing CAR-T therapy for glioblastoma only had one target, which is how the therapy has worked in blood cancers.

The cells targeted a protein with a specific mutation, but Maus said that not everyone with glioblastoma had the mutation. What’s more, even in patients who had the mutation, not every one of their tumor cells necessarily had it. “Even if we got the right cells, we didn’t get all of them because other tumors had other targets,” she said.

Expanding an existing therapy

Both phase 1 clinical trials used CAR-T cells that were programmed to attack two targets instead of one, with the hope that multiple targets would better equip the cells to destroy solid tumors.

“It gives you more shots on goal, at targeting the protein, because these are not completely overlapping targets on any given tumor,” said Dr. Vincent Lam, an assistant professor of oncology at the Johns Hopkins Cancer Center, who specializes in immunotherapies and wasn’t involved with either trial.

In Maus’ clinical trial, which included three patients, T-cells were engineered to seek out and attack a protein called EGRF that’s often found in abundance in glioblastoma tumors but is not present in healthy brain tissue. The second target was a variant of EGRF that’s also commonly found in the tumors.

When used to treat blood cancer, CAR-T cells are transferred back into the body intravenously. Maus’ team chose a more targeted approach for their experimental therapy: injecting the cells directly into the cerebrospinal fluid that surrounds the brain and spinal cord.

This prompted more of the cancer-fighting cells to stick around the site of the brain tumors and, the researchers hypothesized, would reduce the amount of the immunotherapy elsewhere in the body.

Confining the therapy to the brain was important: While the target, EGFR, is not found in healthy brain tissue, it is found in healthy cells elsewhere in the body. If the CAR-T cells went beyond the brain, they could potentially attack these cells.

To further prevent the CAR-T cells from escaping, the researchers bulked them up by binding them to an antibody, which made it more difficult for the cells to cross the blood-brain barrier and enter the bloodstream.

All three patients — two who were in their 70s and one in her late 50s — responded quickly to the treatment. Brain scans showed their tumors shrunk significantly within a day of receiving the therapy. In the 57-year-old woman, an MRI taken five days after her infusion of the modified cells showed her tumor was nearly gone.

The results, however, were temporary.

“We’re still in the early phases of the study. Two patients had their disease recur in the first six months and we want to aim for something better,” Maus said.

While some CAR-T cells did pass beyond the brain, they didn’t do so in large enough numbers to cause damage, the trial found.

Striking a balance

The other trial, published in Nature Medicine, included six patients with recurrent glioblastoma. Their CAR-T cells also sought out EGFR, but used another protein, called IL13Rα2, which is found in 75% of glioblastoma tumors, as their second target.

All six patients underwent radiation to shrink their tumors before they started the immunotherapy, and each was given a single injection of the cells.

The team also delivered the immunotherapy locally, injecting it directly into the cerebrospinal fluid. All of the patients saw a reduction in their tumor size within the first two days of treatment, and they also experienced a significant spike in active CAR-T cells in their spinal fluid for several weeks after injection, meaning the cells were successfully dividing as well as concentrating in the area surrounding tumors.

“That was striking to us. We didn’t expect that kind of expansion, proliferation and maintenance in the spinal fluid,” said Dr. Donald O’Rourke, director of the Glioblastoma Translational Center of Excellence at the Abramson Cancer Center at Penn Medicine in Philadelphia, who co-led the trial.

O’Rourke and his team also used two different doses to get closer to an understanding of what the ideal number of CAR-T cells is for an infusion.

The ideal number would provide the most potent therapeutic effect without causing side effects so severe they negate the cancer-killing benefits, but striking a balance is tricky.

CAR-T therapy is different from a regular drug; it’s considered a “living drug” because the modified cells keep dividing once they’re in the body, meaning the amount in the initial infusion isn’t the final amount a patient will have, O’Rourke said.

All immunotherapies come with risk of neurological side effects, including confusion, language difficulties and sleepiness. The trial found that these side effects came on more quickly when CAR-T cells were injected into the cerebrospinal fluid, but that starting with a lower dose may be able to remedy this. The first three patients were given a lower dose of CAR-T. While they did experience signs of neurotoxicity, it was milder than the neurotoxicity in the three who received the higher dose.

Participants in both trials did experience at least some side effects of CAR-T therapy, which included fever and vomiting as well as neurological effects such as aphasia.

The two trials come just a week after the results of another CAR-T therapy clinical trial for glioblastoma were published in Nature Medicine. That trial used a single target, IL-13Rα2 — also used in the Penn Medicine trial — in 65 patients and also determined that CAR-T therapy is safe and could be an effective treatment for glioblastoma.

Lam, of Johns Hopkins, said that CAR-T has shown promise in glioblastoma in studies over the past five years. The biggest takeaway the two newest trials bring to the table, he said, is that CAR-T therapy appears to be able to safely target two proteins commonly found in glioblastoma tumors.

The question now is whether the results are durable. The results of the early trials don’t necessarily mean the therapy will work long term.

Both teams plan to continue with their ongoing phase 1 trials and modify their approach to home in on the best combination of treatments for glioblastoma.

Maus said she believes CAR-T therapy may be more effective if a tumor is first weakened by radiation and chemotherapy. Other researchers are also exploring cancer-fighting vaccines, which may be able to be used in tandem with CAR-T therapy.

“We’re learning from each other. I think that’s really a tremendous model, and what we are all seeing is that this sort of therapy has legs for brain tumor patients,” Maus said. “It may not be the final version yet, but we’re onto something.”