The culture wars have a new target: your teeth.

Communities across the U.S. are ending public water fluoridation programs, often spurred by groups that insist that people should decide whether they want the mineral — long proven to fight cavities — added to their water supplies.

The push to flush it from water systems seems to be increasingly fueled by pandemic-related mistrust of government oversteps and misleading claims, experts say, that fluoride is harmful.

“The anti-fluoridation movement gained steam with Covid,” said Dr. Meg Lochary, a pediatric dentist in Union County, North Carolina. “We’ve seen an increase of people who either don’t want fluoride or are skeptical about it.”

There should be no question about the dental benefits of fluoride, Lochary and other experts say. Major public health groups, including the American Dental Association, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, support the use of fluoridated water. All cite studies that show it reduces tooth decay by 25%.

“Drinking fluoridated water keeps teeth strong and reduces cavities,” the CDC said in a statement to NBC News.

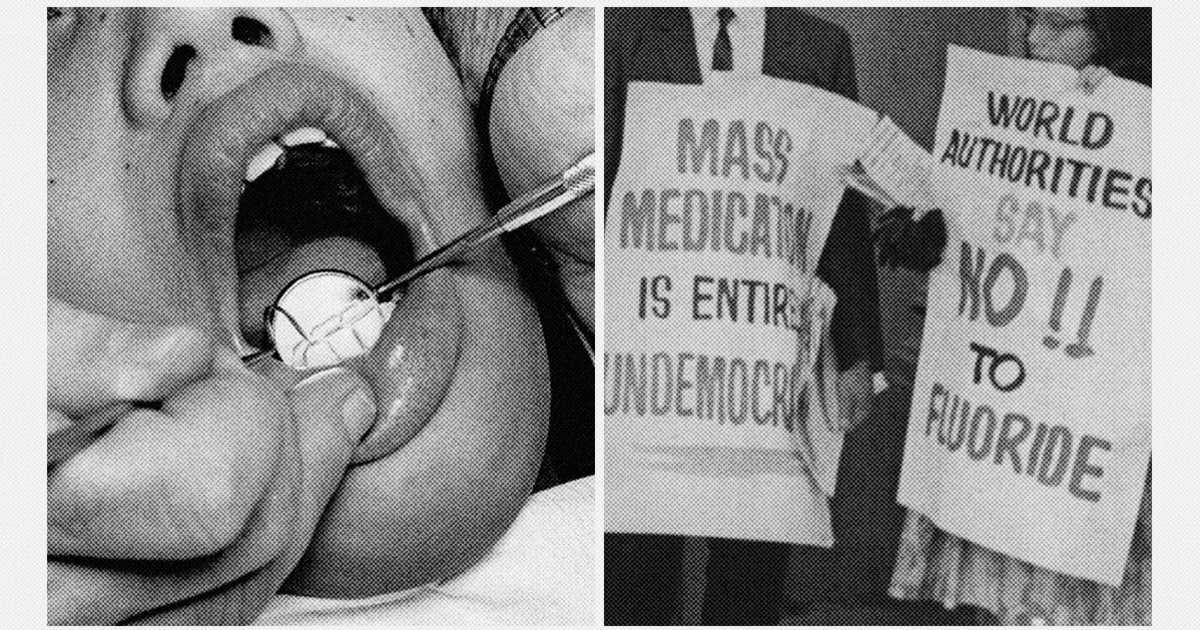

Still, the resistance to fluoride has been building for decades. More recently, the sticking point is about control.

It wasn’t “whether fluoride was good or bad,” said Brian Helms, a Union County commissioner who voted against adding fluoride to the local water supply in February. “The real deciding factor for my vote was a matter of consent.”

He and others were swayed by people like Abigail Prado, the chair of a right-wing group called Moms For Liberty, who questioned the addition of fluoride in public water systems at Union County hearings on the issue.

“It’s the only treatment that the government just mass issues to its citizens,” Prado said in an interview. “That’s not right.”

Union County, just south of Charlotte, is just the latest community to reject fluoridated water. Since 2010, more than 150 towns or counties throughout the country have voted to keep fluoride out of public water systems or to stop adding it, according to the Fluoride Action Network, an anti-fluoride group.

Lawmakers in Georgia, Kentucky and Nebraska have filed bills that would end fluoride mandates in some of their larger communities. Within the past few months, local leaders in Collier County, Florida, and Amery, Wisconsin, voted to stop adding fluoride to public water systems. Last year, lawmakers in State College, Pennsylvania, and Brushy Creek, Texas, did the same.

A federal judge in California is considering whether that research should stop health officials from adding fluoride to drinking water. There have been more than 100 lawsuits over the years trying to get rid of fluoride, without success, according to the American Fluoridation Society, an advocacy group.

The anti-fluoride movement is troubling to doctors who treat children and others vulnerable to tooth decay.

“Community water fluoridation was revolutionary in terms of how it improved the oral health and dental health in our country,” said Dr. Charlotte Lewis, a professor of pediatrics at the University of Washington School of Medicine, with the “most dramatic effect in those populations that are lower-income and have less access to dental care.”

“I think we’re going to take big steps backwards,” she said.

How does fluoride work? How did it become the ‘bad guy’?

Bacteria in the mouth make acid, which weakens teeth and leads to decay. Fluoride counters that process in two ways: It reduces the amount of cavity-causing acids in saliva and strengthens enamel, the tooth’s protective outer layer.

Applying fluoride directly to the teeth through toothpaste or rinses is important, but Lochary said small amounts circulating in the body are critical for young kids who still have their baby teeth.

“Prior to the age of 6, you need to have some fluoride that you swallow so that it can get into the developing permanent teeth,” she said. “That’s the most important time for systemic fluoride.”

It was in the early 1900s that experts first suspected something in the environment was affecting teeth. A dentist who moved from the East Coast to Colorado Springs, Colorado, noticed that people born in the area had dental anomalies he’d never seen before: teeth that were stained with dark brown spots but highly resistant to decay.

Experts eventually discovered that the water in Colorado Springs had unusually high levels of fluoride — up to 12 milligrams per liter. Fluoride is a mineral found naturally in rocks, which then leaches into soil, rivers and lakes.

Grand Rapids, Michigan, became the first community in the world to add fluoride to its water supply in 1945. Within a decade, cavities among young children in the town had plummeted by 60%.

Despite the dramatic reduction in cavities in kids, the Grand Rapids program was mishandled from the beginning. Residents weren’t immediately told that fluoride had been added to their water supply, leading to distrust in local lawmakers and their ability to make appropriate decisions about additives in the water. That triggered a pushback against fluoride in drinking water that has continued.

In 2015, the U.S. Public Health Service, under the Department of Health and Human Services, set the optimal level of fluoride in water at 0.7 milligrams per liter — a level that, after decades of real-world use, experts said, would help protect teeth without staining them.

As of this year, nearly two-thirds of the U.S. population with public water access use drinking water with fluoride, according to the CDC.

A dramatic difference

The positive impact of fluoride on kids’ teeth is easy to see, said Dr. Frank Courts, a pediatric dentist who has had offices in Ashe County, a rural community in Western North Carolina’s Blue Ridge Mountains, and in Nash County, a rural area east of Raleigh.

“The difference between the level of tooth decay in children is dramatic,” he said.

His very young patients in Nash County tend to have fewer and smaller cavities. In Ashe County, children are significantly more likely to have permanent teeth so badly decayed that they have to be pulled before middle school, he said.

“Kids in high school have black front teeth,” Courts said of his practice in the western mountain region. “We see many young adults that have all their teeth already extracted and are wearing dentures in their 20s.”

Just over 10% of kindergartners in Nash County, which has added fluoride, had been treated for tooth decay in 2022-2023, according to the state Department of Health and Human Services. That percentage swelled to more than 44% in Ashe County, whose residents largely rely on nonfluoridated well and spring water.

Both counties have similar income levels and rates of poverty. What explains the difference, Courts said, is that Nash County adds fluoride to its water supply. Ashe County doesn’t.

Even though Medicaid covers oral health for children, only 50% receive those services, said Dr. Julie Morita, executive vice president of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

“People who don’t have access to dental care benefit even more from fluoridated water,” she said. “If they didn’t get fluoridated water, they’d be more likely to get cavities.”

The science behind fluoride

The fluoride issue goes well beyond medical freedom. The latest tactic used by anti-fluoride activists mirrors that of anti-vaccine groups: strike fear in the hearts of moms and dads.

Similar to the anti-vaccine movement, which has focused on disgraced research associating the mumps, measles and rubella shots with autism, groups opposed to fluoride tend to rely on one study that suggests the mineral is a neurotoxin that lowers children’s level of intelligence.

A 2019 study, published in a well-respected journal, JAMA Pediatrics, found that IQ levels were slightly lower in 3- and 4-year-old children whose mothers had higher measures of fluoride in their urine when they were pregnant. Researchers concluded that pregnant women may want to avoid fluoride.

“We have a possible risk,” an author of the study, Dr. Bruce Lanphear, a professor of health sciences at Simon Fraser University in Canada, said in an interview. “It’s absolutely time for us to hit pause on this strategy.”

Lanphear stopped short of saying fluoride should be pulled from water supplies, and he said more research is needed. No other studies have shown similar findings.

Even though a direct link has never been proven, the damage has been done, said Dr. Charlotte Lewis, a professor of pediatrics at the University of Washington School of Medicine.

“It doesn’t matter how much you try to dispel that,” Lewis said. “The onus is on us to continue to get that information out there. It’s a battle just like it’s a battle with the anti-vax folks.”

Dr. Donald Chi, a pediatric dentist at Seattle Children’s Hospital, said he has had to rethink how he talks with parents concerned about fluoride. The conversation starts not with data, but with empathy.

“There’s a lot of disinformation out there that preys on the vulnerability of parents,” Chi said. “People don’t want information. They just want to talk through it and process it.”

Richard Carpiano, a public health scientist at the University of California, Riverside, said, “This is an unintended consequence of parents being good parents.”

Should pregnant women avoid fluoride?

The American College of Gynecologists and Obstetricians recommends that pregnant women use fluoridated toothpaste and mouth rinses to maintain their oral health, but it doesn’t take a position on fluoridated water.

Dr. Nathaniel DeNicola, an OB/GYN in private practice in Yorba Linda, California, hosts a podcast about possible effects of environmental toxins on pregnancy health.

Microplastics, pesticides and air pollution are some examples. Fluoride isn’t.

“To be honest, fluoride doesn’t really rise to much attention when I’m counseling patients about things to be worried about in their drinking water,” DeNicola said. “Fluoride doesn’t fit in one of those categories we’re worried about.”

Searching for solid evidence

The fluoride opposition argues there has never been a double-blinded, randomized, controlled clinical trial — the gold standard of scientific research — looking at the effects of fluoride on children. Researchers at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, are recruiting 200 children under 6 months old to use either fluoridated or nonfluoridated bottled water in their formula and drinking water. Neither the researchers nor the families will know which kind of water will be given.

“I took that as a particular challenge,” said Gary Slade, a professor of dentistry at the Adams School of Dentistry at UNC-Chapel Hill.

The plan is to follow the children for four years to see how their teeth are developing. While the study isn’t funded to include a look at the kids’ IQ levels, it’s possible the study will expand, Slade said.

“It is a perfect situation to look at the IQ of those children when they turn 4,” Slade said. “We’d still have time to add on that component to this study.”

Lochary said she regularly works to alleviate concerns among families who have heard that fluoride may be detrimental to kids.

“We get people who don’t want fluoride, and their kids will come in with a mouth full of decay. Then they won’t want us to do any treatment,” Lochary said. “I’m like, ‘Listen, dental infections can be very dangerous. You can end up in the hospital.’”