ISTANBUL — Turkey’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, won re-election Sunday after seeing the strongest challenge to his 20-year rule.

Turkish public broadcaster TRT called the presidential election for incumbent President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

State-run news agency Anadolu’s vote count shows Erdoğan leading opposition candidate Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu 52.11% to 47.89% with 98.52% of the vote counted.

“We have completed the second round of the presidential election with the favor of our nation,” Erdoğan said following the tally. “I would like to express my gratitude to my people who made us live this democracy holiday. We will deserve your trust.”

Erdoğan’s apparent triumph in the Turkish Republic’s centenary year comes after one of the most hotly contested presidential elections in recent times.

Voters went back to the polls for the runoff election after Erdoğan and Kilicdaroglu each failed to secure more than 50% of the votes in the first round of voting on May 14.

Although Turkey is a NATO ally and it holds elections, the country of 84 million has slipped further toward authoritarianism under Erdoğan and kept close ties with Russia.

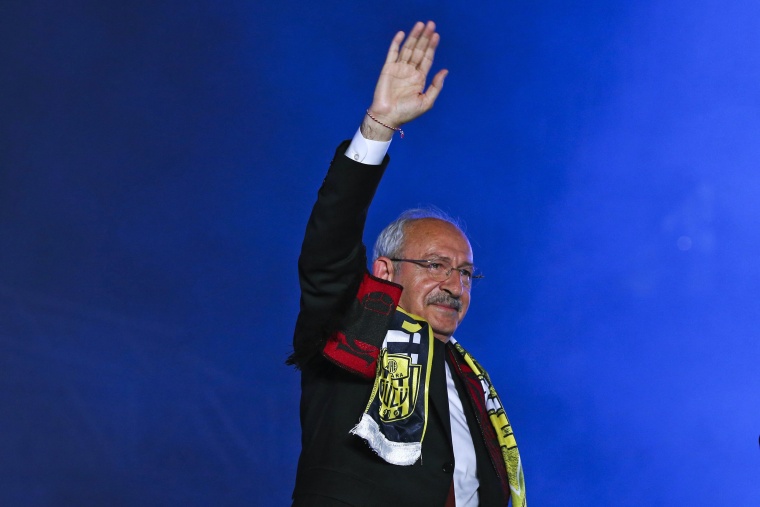

Kilicdaroglu, the joint candidate of an alliance of opposition parties, vowed to reverse the country’s tilt away from democracy.

It was the chance for change in a country where Erdoğan’s AK Party has been in power since 2002. Erdoğan, 69, became prime minister the following year and began serving as president in 2014.

Erdoğan had trailed in opinion polls that followed a campaign dominated by the fallout from the devastating earthquake this year and the country’s economic turmoil. But he led the first round of voting and only narrowly fell short of outright victory.

The steep cost-of-living crisis dominated the agenda, along with a backlash against millions of Syrian refugees as both candidates sought to bolster their nationalist credentials ahead of the runoff.

Kilicdaroglu has led the secular, center-left Republican People’s Party, or CHP, since 2010. He had previously said he intended to repatriate refugees within two years by creating favorable conditions for their return, but he subsequently vowed to send all refugees home once he was elected president.

Erdoğan, meanwhile, courted and won the backing of the nationalist politician Sinan Ogan, the former academic who was backed for president by an anti-migrant party but eliminated after finishing third in the first round of voting.

On the campaign trail, Ogan said he would consider sending migrants back by force if necessary.

Ahead of the first round, Erdoğan also increased wages and pensions, and subsidized electricity and gas bills in a bid to woo voters, while leading a divisive campaign that saw him accuse the opposition of being “drunkards” who colluded with “terrorists.” He also attacked them for upholding LGBTQ rights, which he said were a threat to traditional family values.

Turkey also held legislative elections on May 14, and Erdoğan’s alliance of nationalist and Islamist parties won a majority in the 600-seat Parliament. As a result, some analysts suggested this would give him an advantage in the second round because voters were unlikely to want a splintered government.

Kilicdaroglu, a soft-spoken 74-year-old, built a reputation as a bridge builder and recorded videos in his kitchen in a bid to talk to voters during the campaign.

His six-party Nation Alliance promised to dismantle the executive presidential system narrowly voted in by a 2017 referendum. Erdoğan has since centralized power in a 1,000-room palace on the edge of Ankara, and it is from there that Turkey’s economic and security policies and its domestic and international affairs are decided.

Along with returning the country to a parliamentary democracy, Kilicdaroglu and the alliance have promised to establish the independence of the judiciary and the central bank, institute checks and balances and reverse the democratic backsliding and crackdowns on free speech and dissent under Erdoğan.

The results will have myriad ramifications outside Turkey, which enjoys a strategic location at the crossroads of Europe and Asia. Despite being a NATO member, the country has maintained close ties with Russia and blocked Sweden’s membership in the Western military alliance.

Turkey boasts NATO’s second largest armed forces after the U.S., it controls the crucial Bosporus Strait and it is widely believed to host U.S. nuclear missiles on its soil.

Together with the U.N., Turkey brokered a vital deal that has allowed Ukraine to ship grain through the Black Sea to parts of the world struggling with hunger.

Neyran Elden reported from Istanbul and Henry Austin from London.