The scenes are part of a 2-minute video Kastyukevich posted on the Telegram messaging app showing Russian officials and their local allies removing young children from the Regional Children’s Home in Kherson in late October, weeks before it was liberated by Ukrainian forces. Dozens of children were taken to “safety,” he said.

According to Kyiv, the video is evidence in a growing case against the Kremlin for its alleged war crimes in Ukraine. The country accuses Moscow of abducting tens of thousands of its children and shipping them to Russia with the intent of stripping them of their national identity, a crime that Ukrainian officials call a form of genocide. Russia denies allegations of war crimes, and says it has evacuated close to 2 million civilians, including hundreds of thousands of children, from what it said were dangerous areas of Ukraine.

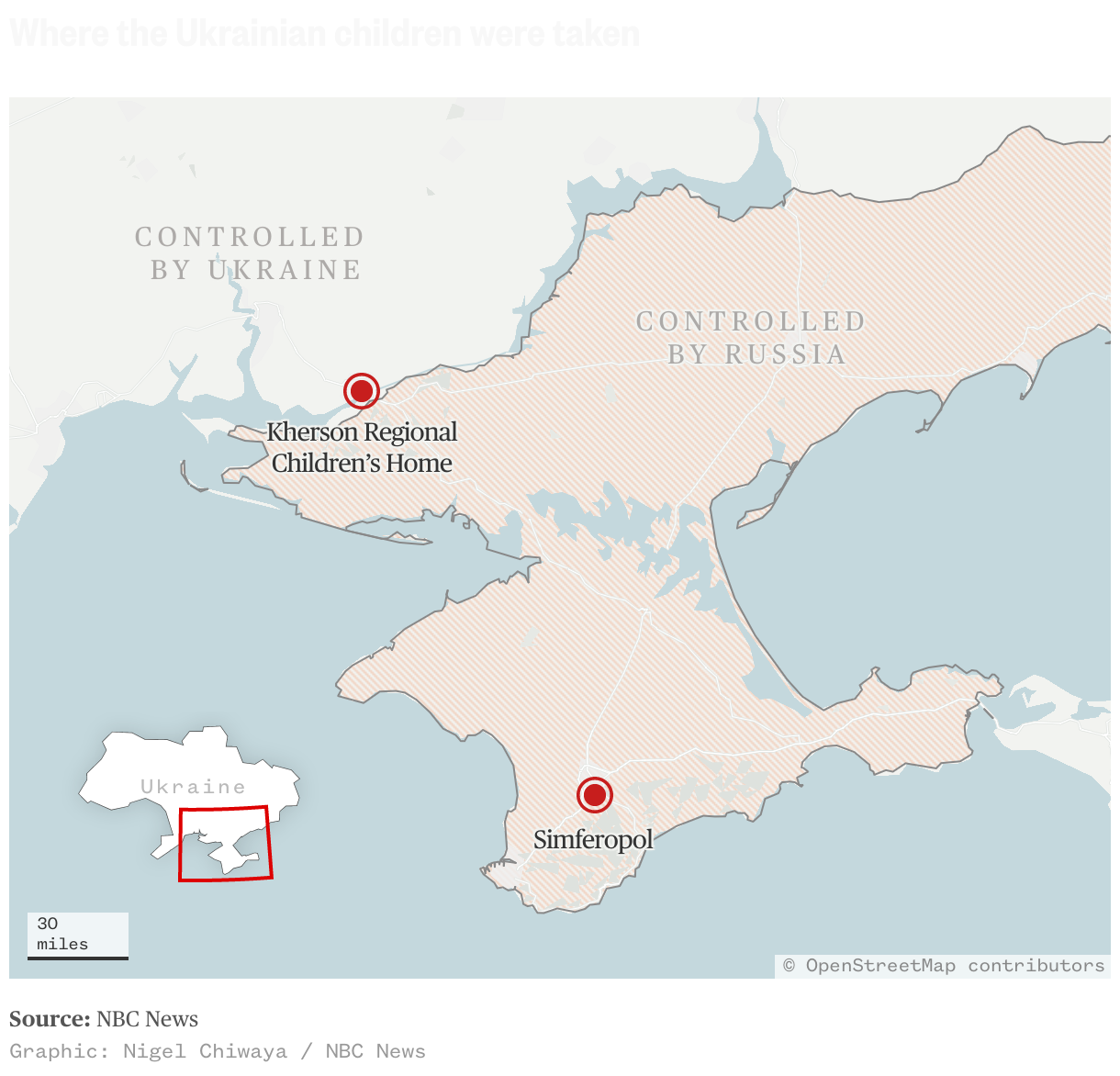

In a caption to the video, Kastyukevich said the children were “evacuated” and moved to the nearby Crimean Peninsula, occupied by Russia since 2014. Around the same time, Russia was trying to evacuate thousands of residents from Kherson in the face of a looming Ukrainian offensive.

“We have saved them,” Kastyukevich wrote.

Ukrainian officials in Kherson immediately called it a “kidnapping.”

Very little is known about what happened to the children, but senior Russian officials told NBC News that they are still in Crimea. They say no one has come looking for them.

Ukrainians dispute this, saying they are working to bring the 48 children home, but fear they could disappear into Russia.

On Friday, Ukraine formally charged Kastyukevich, who shared the video of the children’s evacuation, as well as an ex-worker at the orphanage and an official in the region, accusing them of the illegal transfer and deportation of the children from the facility.

NBC News has contacted Kastyukevich about the charges but did not receive a reply.

The young children from the Kherson Regional Children’s Home are not the only children who have disappeared.

Ukraine says it has documented nearly 20,000 cases of deported or forcibly transferred children. But that number could be as high as 300,000, according to the Ukrainian president’s adviser on child rights, Daria Herasymchuk.

In an unprecedented move against the leader of a permanent United Nations Security Council member state, the International Criminal Court (ICC) issued arrest warrants for Putin and his children’s representative, Maria Lvova-Belova, in March. Prosecutors at the Hague-based war-crimes court accused them of “unlawful deportation and transfer of Ukrainian children” from occupied areas of Ukraine to Russia, including “the deportation of at least hundreds of children taken from orphanages and children’s care homes.”

Moscow has dismissed accusations that it illegally deports Ukrainian children, and Russian officials have touted cases where they say they rescued children from active fighting. Last month, Putin said that his forces have legally moved “entire orphanages,” saving children’s lives, and that Moscow has never been against reuniting Ukrainian children with their families.

Lvova-Belova, who has said in multiple Telegram posts that she is now the foster parent of a child from Mariupol, a city devastated by Russia’s war, has borne the brunt of international scrutiny. In many ways, she has become the face of a new type of alleged war crime.

The babies from the Kherson Regional Children’s Home are not the only children who have disappeared during the Ukraine-Russia conflict. (Bernat Armangue / AP file)

The babies from the Kherson Regional Children’s Home are not the only children who have disappeared during the Ukraine-Russia conflict. (Bernat Armangue / AP file)

Her social media feeds are full of videos of Russian foster families greeting Ukrainian orphans, whom she has personally delivered across the country, with balloons and toys.

Lvova-Belova says she visited the children from the Kherson Regional Children’s Home in a home in Crimea shortly after they were removed from Ukraine, and promised to find their relatives.

Russian Presidential Commissioner for Children’s Rights, Maria Lvova-Belova, transporting orphans from the Donetsk People’s Republic in Sept. 2022. (Kremlin.ru)

Russian Presidential Commissioner for Children’s Rights, Maria Lvova-Belova, transporting orphans from the Donetsk People’s Republic in Sept. 2022. (Kremlin.ru)

She did not respond to a request to visit the children in Crimea, but did tell NBC News that her office was actively looking for their relatives in Ukraine. The children would not be put in foster care or up for adoption until that search had been exhausted, she says.

Ukrainian officials looking into the case disputed her claim that no one is looking for the missing children.

Mykola Kuleba, CEO of Save Ukraine, a leading nongovernmental organization that helps deported Ukrainian children return home, said the organization had identified the children taken from the Kherson orphanage and is looking into the case.

The challenge with a case involving such young children is that they become difficult to trace after being moved into territory occupied by Russia or into Russia itself. Kuleba said the time window to bring them back to Ukraine was shrinking every day because many won’t even know their own names.

“It will be very hard to return them,” he said.

After the ICC issued arrest warrants for Putin and Lvova-Belova — in part to prevent “further commission of crimes” — Kuleba said reuniting children with families had become even more challenging.

“We found that it’s harder and harder to return any child,” he said.

Lyudmyla Afanasieva is a former staff member of the Kherson orphanage and cared for the children while they were in the basement of a church whose pastor had sheltered them during heavy fighting.

The young children, whom Afanasieva said she recognized from the video shared by Kastyukevich, had been “stolen.”

“These are our children,” she said in a telephone interview.

Except for two orphanage staffers, the adults who took them to Crimea were strangers to the children, Afanasieva said.

The overgrown playground of the Regional Children’s Home in Kherson, in 2022. (Chris McGrath / Getty Images file)

The overgrown playground of the Regional Children’s Home in Kherson, in 2022. (Chris McGrath / Getty Images file)

At least three senior Ukrainian officials told NBC News they were actively working on the case: the country’s chief prosecutor, its children’s representative and the human rights ombudsman. They declined to disclose detailed information about the children’s whereabouts or the status of their investigations, saying that doing so would jeopardize their work.

“They moved them farther, most likely. So we are still looking for them,” said Daria Herasymchuk, Ukraine’s Commissioner for Children’s Rights. “But we know exactly who we are looking for. We know the names of these children.”

Like Kuleba, she fears that returning the children will be a challenge.

“If we are speaking about little ones who, in a year, can forget about where they are from, what their names are … it will be very difficult to return these children, but we will fight for every one of them,” Herasymchuk said.

In May, nearly 15 months after Russia’s invasion, Lvova-Belova said that Kyiv had for the first time sent concrete information on 11 children whose parents were looking for them, without providing their locations or further details.

Dmytro Lubinets, Ukraine’s human rights chief, disputed this.

“Thousands of names” had been forwarded to his counterpart in Moscow, Tatyana Moskalkova, who works closely with Lvova-Belova, he said, although he did not provide any documents or other evidence.

Strollers and toys are stacked outside a storage room at the Kherson Regional Children’s Home in November 2022. (Chris McGrath / Getty Images file)

Strollers and toys are stacked outside a storage room at the Kherson Regional Children’s Home in November 2022. (Chris McGrath / Getty Images file)

At least 373 children have been returned to Ukraine without Russian help, Lubinets said. He declined to provide more information on how they were returned, saying that doing so would compromise future operations.

Ukrainian officials allege that abducted children are being put up for adoption by Russian families. Moscow denies that but acknowledges that 380 Ukrainian orphans have been placed with foster families in Russia. Lvova-Belova insists that they have not been formally adopted and that they will be reunited with their families in Ukraine if the families look for them.

In fact, she says, all that families or legal guardians have to do is write an email to her office to start a search. Her claim runs counter to statements from Ukrainian officials and families, who say they have to devise a new rescue mission for every child.

The Russians are doing “everything” to block their efforts to get the children back, Lubinets said.

Ukraine’s prosecutor general, Andriy Kostin, whose office is investigating some 90,000 cases of alleged war crimes, said the deportation of children is a special case.

The Russians are intentionally keeping Ukrainian children as “hostages,” refusing to return them and stripping them of their identities, Kostin told NBC News in an interview.

“This is the type of crime which is so far from the war,” he said. “It’s not about the war itself. It’s about the intention to steal children from the Ukrainian nation.”

Molly Hunter, Brock Stoneham, Ed Flanagan and Ostap Hunkevych contributed reporting.

Design and Development

JoElla Carman

Photo Editor

Max Butterworth

Art Director

Chelsea Stahl