A rare fungal infection thought to mainly occur in the northern Midwest and parts of the Southeast is more common in other parts of the U.S. than expected, new research published Wednesday finds.

The illness, called blastomycosis, can be difficult to diagnose, in part because it can resemble other respiratory infections. And the longer it goes undiagnosed, the more difficult it is to treat.

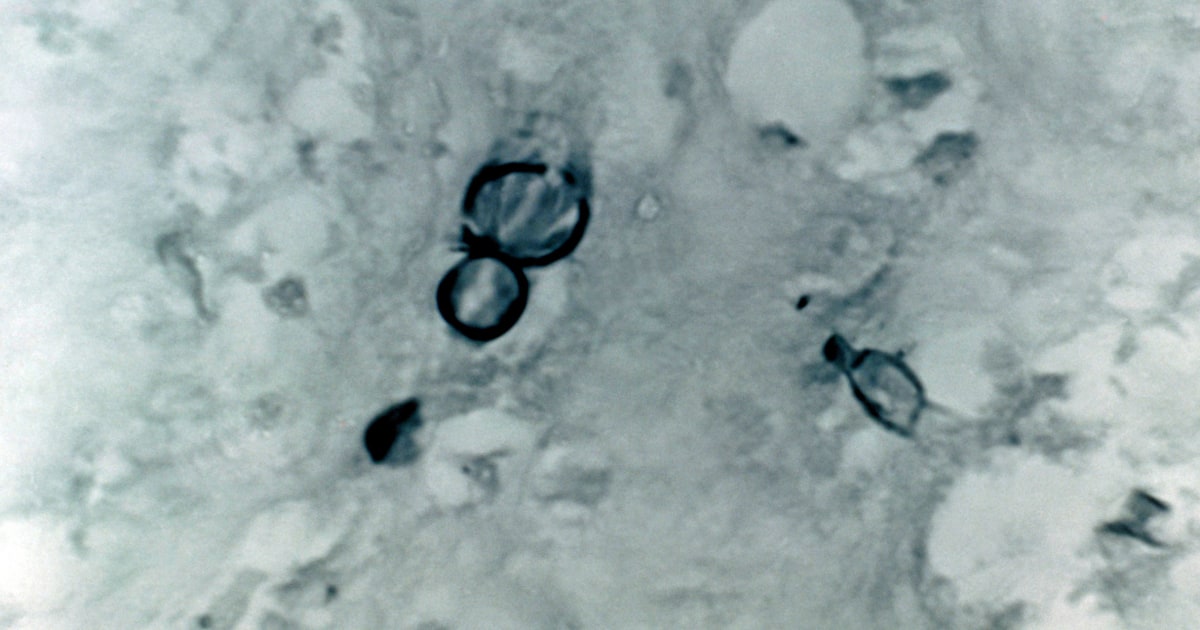

The infection is caused by a fungus called Blastomyces dermatitidis, which thrives in wet soil and decaying logs and leaves. Blastomycosis is considered an “endemic mycosis” — a type of fungal disease that only occurs in a particular geographic area.

While it’s well known in areas around the Great Lakes, the Ohio River valley and the Mississippi River valley, it’s a bit more surprising for the infection to pop up in Vermont, but that’s exactly what was found in the new study, published in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Emerging Infectious Diseases journal.

“Vermont is not generally an area you think of when you talk about blastomycosis,” said Dr. Arturo Casadevall, chair of molecular microbiology and immunology at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. But “there have been several papers recently suggesting that fungal infections are on the move across the country and this is one of them.”

Dr. Brian Borah, medical director for Vaccine-Preventable Diseases Surveillance at the Chicago Department of Public Health, who led the study, said, “It’s a big question whether we were able to detect cases that were unknown to us previously, or if we are detecting an increase in cases.”

The epidemiology of other fungal diseases nationwide has been changing, however, Borah said, adding, “I don’t think blastomycosis would be immune from those patterns.”

Blastomycosis is rare, and can cause respiratory symptoms, fever and body aches in about half of the people who are infected from inhaling the Blastomyces spores. Most cases are mild, but if left untreated, blastomycosis can cause serious illness or death.

“One of the great problems with fungal diseases is that they are unreportable,” meaning public health departments don’t require doctors to report cases of the illness they see to the state, said Casadevall, who was not involved with the new study.

Only five states — Arkansas, Louisiana, Michigan, Minnesota and Wisconsin — have public health surveillance for blastomycosis. That means the prevalence of the disease outside these states is unknown.

Borah, who was previously a CDC epidemic intelligence service officer assigned to the Vermont Department of Health, said that there had been some reports of blastomycosis cases in the Northeast, including from a couple of studies as well as anecdotal reports from doctors and veterinarians in Vermont.

Without public surveillance, Borah and his team turned to health insurance claims to determine how many patients were treated for blastomycosis in Vermont from 2011 through 2020.

The data included all claims from Medicare and Medicaid recipients in the state and about 75% of Vermont residents who had other health insurance. They identified 114 cases during the 10-year period, and 30% required hospitalization. With an average rate of 1.8 cases per 100,000 people every year, Vermont had higher rates of blastomycosis than all but one of the states that have surveillance for the disease, the study found. Wisconsin, the state with the highest rate of blastomycosis, has an average of 2.1 cases per 100,000 people.

Gaining new ground

A study published in 2022 suggested that around 10% of illnesses caused by fungal infections were diagnosed outside regions where the fungi are known to be endemic.

There are a number of things that could be happening, said Dr. Bruce Klein, a professor of pediatrics, medicine and medical microbiology and immunology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. These pathogens can hitch a ride on shoes when people travel. New developments can stir soil — and the fungi they harbor — releasing spores into the air in places they weren’t thought to exist.

“Blastomyces dermatitidis grows as a mold and the mold produces spores. When those spores are physically disturbed, they become aerosolized and are breathed into the lungs,”Klein said, adding that wind and rain, not just human intervention, can cause the spores to become airborne.

Recent studies have shown that climate change is also expanding the ranges of fungi that can make people sick. Human-driven climate change is shifting rain patterns, increasing drought in some regions — an environment that favors fungi including Coccidioides, which causes Valley fever — while causing more flooding and humidity in others.

Rising temperatures and extreme weather events including storms, flooding, drought and hurricanes, impact soils and can redistribute fungi, said Asiya Gusa, an assistant professor of molecular genetics and microbiology at Duke University who studies how fungi adapt to heat stress.

“That is going to increase our human exposure to fungi and also expose those fungi to higher temperatures,” she said. “There’s a fear that with increased humidity and warm, damp weather, we could see a larger accumulation of spores.”

Early studies have suggested that heat could put stress on fungi that thus far have not been able to withstand body heat, to evolve to be able to survive in the human body.

“Climate change is the 800-pound gorilla in the room,” Casadevall said. “That could change a lot of the epidemiology of these diseases.”

Difficult to diagnose

Once Blastomyces dermatitidis spores enter the lungs, a person’s body heat triggers a shape-shifting transformation. The spores morph into yeast cells protected by thick armor, which is one reason fungal infections can be so difficult to treat, Klein said.

Another reason is that fungal cells are much more like human cells than plant cells or bacterial cells, which makes it difficult to develop drugs that can attack and kill fungi without also damaging human cells, he said.

Fungal infections are most concerning for people who are immunocompromised, and most serious fungal infections occur in this population. But blastomycosis usually occurs in otherwise healthy people, Klein said.

“This is a remarkable distinction from many other fungi that are more feeble and prey on people whose immune systems are impaired by things like biologics,” he said, noting that two other fungal diseases — Valley fever and histoplasmosis, which are also found in specific regions in the U.S., also behave like this.

There is likely a dose-response, meaning the more spores a person breathes in, the greater chance they have of getting sick. The fungus is usually found in small pockets, often in damp woods, meaning people are not exposed to it all the time, Klein said.

Most blastomycosis cases are mild. About 95% are fully treatable with antifungals, but it can take up to a year to clear an infection that’s spread outside the lungs, Klein said.

The difficult thing is that fungal infections often look like other illnesses and can go undetected for weeks or months. This is especially true in places where fungal infections including blastomycosis and Valley fever aren’t thought to occur.

“Most commonly, these infections can look like garden-variety pneumonia or another respiratory illness,” Klein said. “These are more common than blastomycosis, so people are usually treated first for these other problems and they can see a physician, once, twice, three times, getting different courses of antibiotics while the fungal infection progresses.”