The Summary

- Roughly one-third of former professional football players surveyed believe they have CTE, a study found.

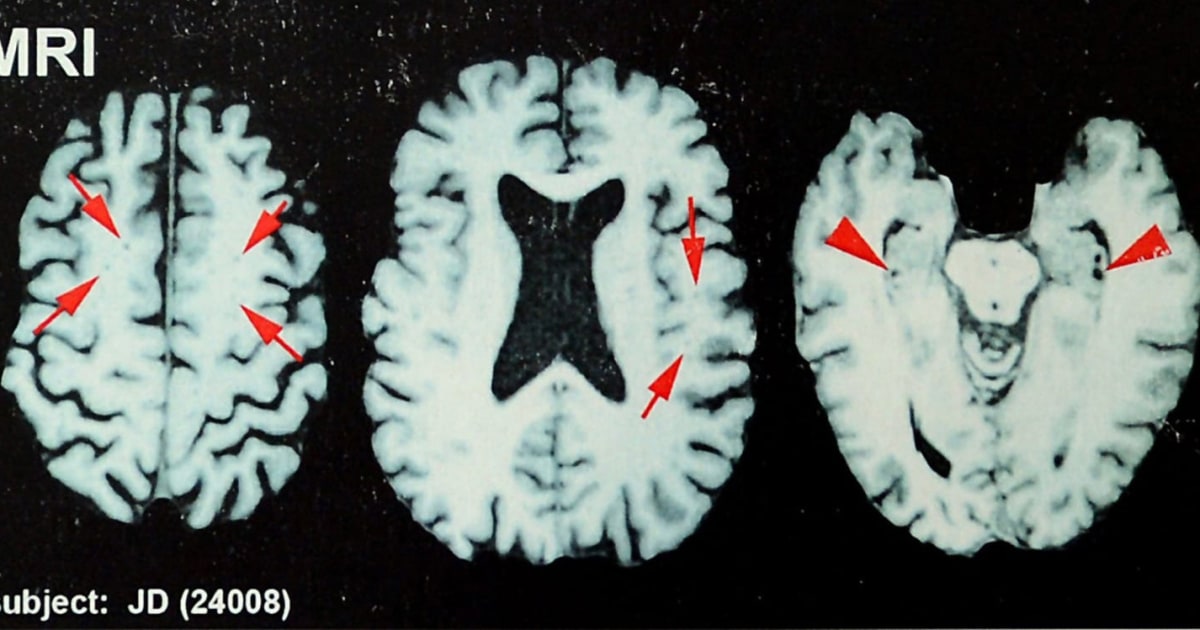

- The brain disease — which is linked to repeated hits to the head — can be officially diagnosed only after death.

- But the new research indicates many former NFL players have experienced symptoms associated with CTE, including depression and cognitive difficulties.

Roughly one-third of former professional football players surveyed believe they have chronic traumatic encephalopathy, according to a recent study.

The brain disease, better known as CTE, is linked to repeated hits to the head. Evidence of it has been found in the brains of many former football players after death.

The research, published Monday in the journal JAMA Neurology, is distinct from many other studies on CTE in that it is based on survey data from former players who are still alive, even though CTE can only be officially diagnosed via an examination of the brain postmortem.

“Most of the studies that have been done on CTE are much smaller studies on deceased players,” said Rachel Grashow, the lead author of the new study and director of epidemiological research initiatives at Harvard University’s Football Players Health Study. “So, we have this incredibly rich cohort. It is diverse by geography, by race, by amount of playing time. We are studying, really, how they lived their lives, not postmortem.”

The Football Players Health Study — the cohort Grashow is referring to — is funded in part by the National Football League Players Association, as is some of Grashow’s work. The project surveyed around 4,000 men who played in the American Football League and National Football League between 1960 and 2000 (the two merged in 1970). Their responses were collected from 2017 to 2020.

The new study focuses on a subgroup of just under 2,000 respondents who provided additional data. Of those, 34% said they believed they had CTE, based on symptoms they had experienced, including depression, cognitive difficulties and long-term effects of previous head injuries.

The NFL did not respond to a request for comment.

CTE is characterized by the death of nerve cells in the brain, which can lead to cognitive impairment, difficulty regulating behavior, mood changes and depression, including a higher risk of suicidal thoughts. Symptoms can take years or decades to develop after head trauma. Researchers think the risk of CTE increases when a second head injury is sustained before an initial one heals.

Of the 681 respondents with perceived CTE in the new study, a quarter reported suicidality, compared with just 5% among respondents who did not believe they had CTE.

Grashow said a key finding of her research was that many of the symptoms and conditions that respondents with perceived CTE reported were treatable, such as depression and sleep apnea.

“Once you start to talk about treating these different conditions and getting them to go to the doctor and asking about them, the conversation totally shifts from, ‘Do they or do they not have this incurable, unknowable neurodegenerative disease?’ to, ‘What can be fixed now?’” Grashow said.

She added that treatments and management plans have generally not been a part of the CTE conversation in the past.

“What does CTE look like on an autopsy if they manage their hypertension, if they manage their depression, if they manage their sleep apnea and if they manage their pain?” she said.

Dr. Thor Stein, director of molecular research at Boston University’s CTE center, said treating and managing CTE symptoms among those who suspect they might have it is a viable path.

“There are a lot of symptoms that sometimes are thought to be CTE, but they can still be treated,” he said. “It’s important to identify the ones you can treat and get treatment as soon as possible. I don’t think that undermines the fact that CTE exists, and it still is something we want to try to understand more.”

In the future, Stein said, researchers hope to pinpoint biomarkers that can help guide CTE diagnosis in living patients.

He added, however, that the new study has gaps, since it relied on self-reported responses.

“This was a single survey based on just a limited number of questions and I think it wasn’t really validated by clinical follow-up. That’s important to do, but I think it’s a really important first step,” Stein said.

The new research came in the first month of the NFL season, and less than two weeks after Miami Dolphins quarterback Tua Tagovailoa sustained a concussion in a game against the Buffalo Bills. It was Tagovailoa’s third concussion of his five-year NFL career.

That incident renewed questions about the league’s role and responsibility in its players’ risk of CTE. The NFL in 2016 acknowledged a link between football and CTE, and the league agreed to settle thousands of player lawsuits over head injuries for $765 million in 2013.

Over the last few years, the NFL has introduced new position-specific helmets and an additional, padded layer of protection called a guardian cap that is worn over the helmet during practices with contact.

Guardian caps are optional in games this season, and few players have chosen to wear them. Indianapolis Colts tight end Kylen Granson is an exception.

“For me, it was a no-brainer. I just said yes. I want to wear it the whole season,” he said in a video on TikTok, adding, “Anything I can do to mitigate any sort of brain injury or long-term health effects that would be detrimental to me takes precedent.”