The Summary

- An advanced diagnostic test uses genetic sequencing to detect a variety of pathogens — viruses, bacteria, fungi and parasites — that might be causing an illness.

- A new study found that it has been effective at identifying the cause of neurological infections like meningitis.

- The test is not yet FDA-approved, and it is expensive to run, but its creators hope it is used more broadly in the future.

A cutting-edge diagnostic test is helping some doctors find diagnoses for medical mysteries by analyzing DNA and RNA to detect a broad swath of viruses, bacteria, fungi and parasites, according to a pair of studies published Tuesday.

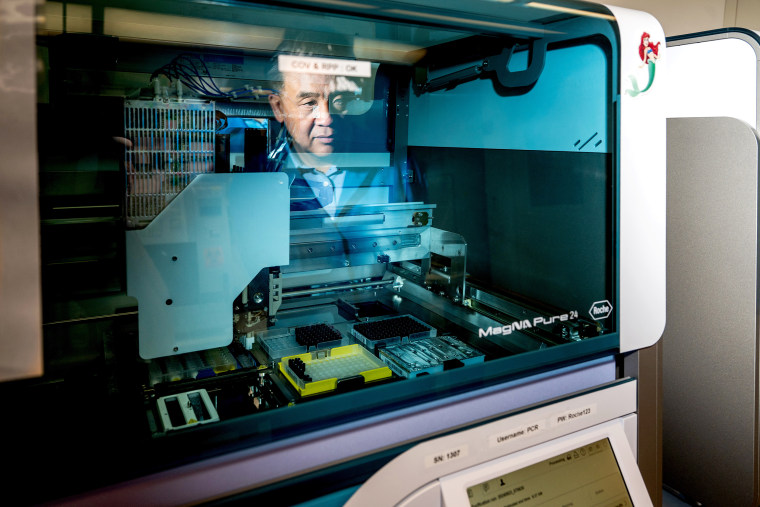

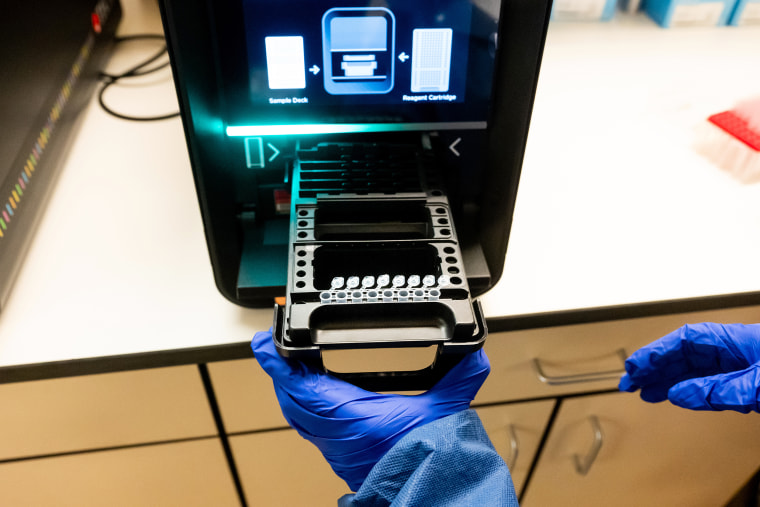

Traditional diagnostic tests are generally designed to measure specific substances such as proteins, hormones or trace amounts of genetic material. But the genomic test, developed at the University of California, San Francisco, instead extracts all the DNA and RNA present in a sample of blood, tissue or body fluid, then sequences that genetic material. It compares the sequences to a vast database of pathogens to see what matches up.

The technology is not a replacement for existing tests used to diagnose common illnesses — like those for Covid or strep throat — since it’s slower to deliver results and more expensive. But it shows promise in a particular scenario: when a patient is in the hospital with severe symptoms, but initial tests come back negative and doctors can’t figure out what’s wrong.

Already, the test has been effective at identifying the cause of neurological infections such as meningitis and encephalitis (swelling of the brain or its surrounding membranes), according to one of the new studies, published Tuesday in the journal Nature Medicine. Using samples of spinal fluid, it was able to diagnose 86% of the neurological infections it encountered out of more than 4,800 samples gathered at UCSF over a roughly seven-year period.

In 2021 and 2022, the test was able to link cases of encephalitis among transplant recipients to yellow fever in their organ donor. And last year, it helped pinpoint the cause of a meningitis outbreak among patients who had undergone surgical procedures in Mexico.

“Our test was used to identify the cause of it as a specific fungus, Fusarium solani, from one of the early patients who had become symptomatic,” said Dr. Charles Chiu, a professor of laboratory medicine and infectious diseases at UCSF and the senior author of the new study.

The second study on the test, published Tuesday in the journal Nature Communications, suggests it could also be used to detect novel viruses, including those with the potential to start pandemics. The researchers ran a simulation to see whether the test could pick up on human viruses like the coronavirus that causes Covid, even if the researchers removed those viruses’ genetic sequences from the database on which the test relies.

The test still identified the viruses based on related strains in animals, Chiu said.

The Food and Drug Administration has granted the test a “breakthrough device” designation, which allows labs to use it based on its potential to help patients, even though the agency hasn’t yet approved it. But the test is expensive: Running it costs $3,000 per sample and fewer than 10 labs use it routinely, Chiu said.

“Traditionally, it’s been used as a test of last resort, but that’s primarily because of issues involving, for instance, the cost of the test, the fact that it’s only available in specialized reference laboratories, and it also is quite laborious to run,” he said.

Chiu added that the new research “raises the possibility that we perhaps should be considering running this test earlier” in the course of a person’s infection.

Chiu and his fellow UCSF researchers developed the test 10 years ago. Shortly after, it detected a case of leptospirosis, a bacterial infection, in a 14-year-old boy who was in a medically induced coma. The diagnosis led doctors to prescribe penicillin, after which the boy recovered quickly.

But the test comes with limitations, according to Susan Butler-Wu, an associate professor of clinical pathology at the University of Southern California.

The technology is likely too complicated for the average community hospital to adopt in the foreseeable future, she said. And doctors could have a hard time interpreting the results, so they would need to consult with a laboratory director who has the appropriate expertise.

“This just is not something that a clinical lab will be doing until somebody commercially puts it in a box with an easy button,” Butler-Wu said.

The test also misses some cases, she added, so it should be used alongside other diagnostic tests in hospitals.

“It’s not a one-stop shop,” Butler-Wu said. “It just can be helpful as an additional tool.”

Nonetheless, Chiu said, he could envision the test being used widely in hospitals someday to diagnose all sorts of illnesses, such as the root causes of pneumonia or sepsis.

“We need to get the cost down and we need to get the turnaround times down as well,” he said.