After three miscarriages in less than a year, Gabby Goidel said she was diagnosed with unexplained genetic infertility.

For reasons that aren’t clear to doctors, any fetus she carries has a higher-than-average likelihood of genetic abnormalities, she said, so there is a slim chance she’d be able to carry a pregnancy to term without in-vitro fertilization.

To avoid the possibility of additional miscarriages, Goidel and her husband, Spencer, decided last year to pursue IVF in their home state of Alabama.

IVF allows doctors to test embryos for genetic abnormalities, then implant only the ones that are healthy.

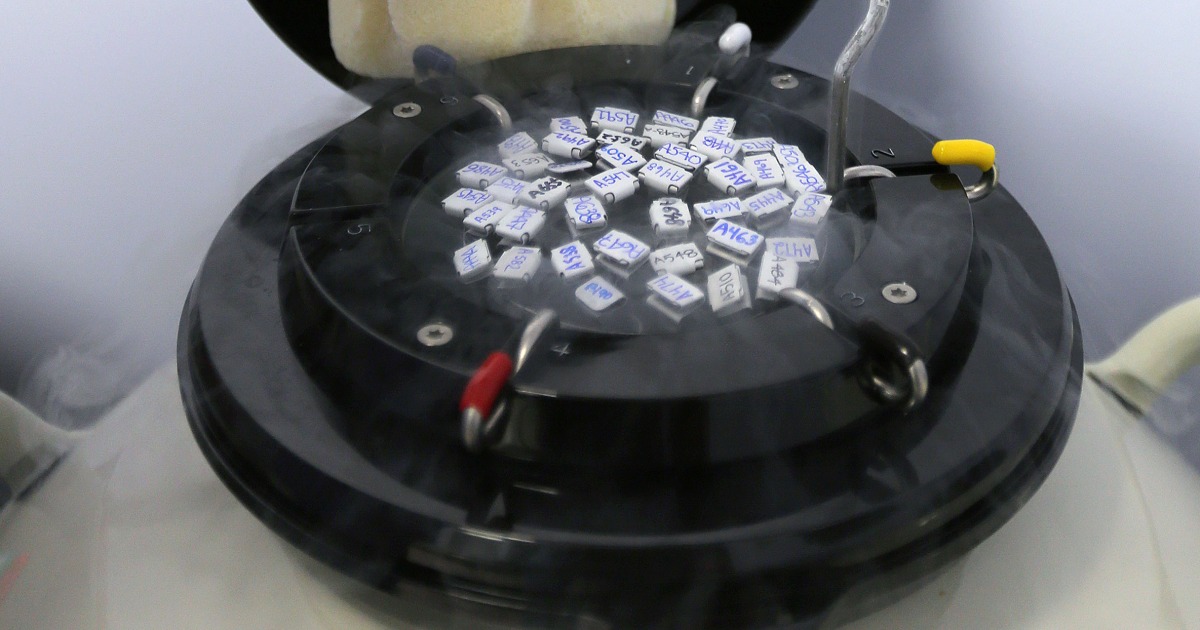

The Goidels were on track to freeze embryos later this month, and they planned to only store the ones that were genetically normal.

But on Friday, the Alabama Supreme Court ruled that frozen embryos created through IVF are considered children under state law, meaning people could theoretically be sued for destroying an embryo.

The Goidels began to worry whether they might be forced to store — or even use — embryos they had intended to discard.

“Most of our embryos are not going to be genetically normal,” said Gabby, a 26-year-old property manager in Auburn. “My hope would be that we could let those embryos naturally pass, but now it’s, ‘Do we have to save them?’ I don’t necessarily want to implant a child that I know is going to miscarry.”

Roughly half of first-trimester miscarriages are due to a chromosomal abnormality in the fetus. In addition to vaginal bleeding, abdominal pain and cramping, miscarriages can increase the risk of anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder and suicide.

An uncertain future for IVF patients

In the wake of the Alabama ruling, many patients and providers are unsure of how to navigate the IVF process, given that embryos are often discarded if they have genetic abnormalities or after patients decide they will not need to use them. The decision raises questions about whether those who undergo IVF will have to store all their embryos indefinitely — but experts said the answer is not yet clear.

Storing frozen embryos can cost between $350 to $1,000 per year.

The court’s decision was issued in a case in which a person removed embryos from storage at a fertility clinic and dropped them on the floor accidentally.

Gail Deady, senior staff attorney at the Center for Reproductive Rights, said that because of that, the ruling “does not appear to create criminal liability for IVF providers.”

Instead, she said, “what it does implicate is the Wrongful Death Act, which is civil liability and negligence,” meaning people could be sued for the destruction of embryos and have to pay monetary penalties.

Nevertheless, “anyone who cares about reproductive autonomy should be terrified of this decision,” Deady added.

Dr. Mamie McLean, a reproductive endocrinologist at Alabama Fertility, said she is concerned about the survival of IVF services in Alabama. Clinics may need to raise prices if they have trouble staffing providers or have to pay more for medical malpractice insurance, she said. As a result, fewer people may be able to afford IVF and fewer insurers may be willing to cover treatments.

The cost of insurance to defend against wrongful death lawsuits “might actually prevent us from practicing, it would be so high,” said Dr. Brett Davenport, a reproductive endocrinologist at Fertility Institute of North Alabama.

Davenport, too, worries the new law could penalize doctors for helping people start families.

“I am a very pro-life reproductive endocrinologist, and yet this still seems quite absurd to me,” he said.

Legal experts worry the ruling could set the stage for harsher abortion restrictions in the future, as well, such as penalties for women who get abortions. (Right now, state law only penalizes providers who administer abortions.)

“The next step will be to say, ‘Well, if an embryo is a person [outside the uterus], clearly it’s a person in utero,” said Priscilla Smith, director of the Program for the Study of Reproductive Justice at Yale Law School.

“I don’t want to be dramatic and say it’s totally Handmaid’s Tale, but more and more, you’re in the situation rather where the state controls your behavior,” Smith said.

Where to put embryos?

After the Alabama Supreme Court decision, Meghan Cole, an attorney in Birmingham, made a plan to move her remaining embryos to another state. Cole has a rare blood disorder that prevents her from safely carrying a child, so she’s planning to use a surrogate. That embryo transfer is scheduled for next week, and she still has other embryos in storage.

“I was scared for what the future held for the embryos that we’re still going to have in storage,” Cole said. “My first thought was, ‘OK, I need to transfer my embryos out-of-state and have them frozen somewhere else so I don’t open myself up to liability.’”

She selected which embryo to use with Alabama’s legal landscape in mind, she said.

“We are picking a boy to transfer because these rules and laws that are coming out that are affecting women’s health kind of scare me for a daughter,” Cole said.

Deady said there’s no reason yet why patients in Alabama should be afraid of getting IVF — but providers are proceeding cautiously.

McLean said there are even some concerns about the ability to freeze embryos in the first place, given the ruling. An alternative to freezing or discarding embryos, she said, would be to create fewer of them. But in that case, patients would likely require more rounds of IVF to get pregnant, which is both expensive and physically demanding.

Alabama’s legal landscape has made the Goidels reconsider whether they want to raise kids there.

“We’re this very traditional family that just wants to have a kid, so I didn’t realize ever that this was going to be a question of morality,” Gabby Goidels said.

“We really envisioned starting a life here and probably retiring here,” she added. “We’re very much questioning whether or not we want to leave.”