It took 12 years for Allison Tuckman to get an accurate diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome, then another 10 to find a treatment to help keep her most severe symptoms in check. Now that she’s finally found a drug that works, the 44-year-old from Manalapan, New Jersey, says there’s no going back. “I’ll be taking it ‘till the end of time,” she said.

That medication happens to be semaglutide, the same drug in high demand largely for its effects on weight loss. It’s approved under the name Ozempic for Type 2 diabetes and under the name Wegovy for weight loss. Semaglutide falls into a class of drugs called GLP-1 agonists, which also includes the diabetes drugs Mounjaro and Victoza, among others.

Since the drugs flooded the scene, there have been reports of other potential uses for them, to treat conditions ranging from PCOS to Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, addiction, alcohol use disorder, liver disease and possibly cancer.

But proving they work for each individual condition means spending years, and a tremendous amount of resources, to conduct meticulous laboratory research and large clinical trials. It also requires access to a reliable supply of these drugs, which is far from a given amid widespread shortages.

“Unfortunately, because of the shortage of supply, Novo Nordisk is focused on manufacturing the drugs for clinical care and not for research studies,” said Dr. Lorezo Leggio, the clinical director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse at the National Institutes of Health, who has been studying these drugs as a potential treatment for addiction and alcohol use disorder.

These constraints have meant the evidence required to get the Food and Drug Administration, insurance providers and even the pharmaceutical companies on board with these new uses has lagged behind the personal experiences of people like Tuckman who say they’ve seen it firsthand: the drugs work.

“These anecdotes of people reporting the beneficial effects of semaglutide are very welcome, but they are not the end of the story,” Leggio said. “Medication development needs rigorous science with gold-standard approaches such as clinical trials.”

Does Ozempic work for PCOS?

Although GLP-1 agonists aren’t FDA-approved to treat polycystic ovary syndrome, Tuckman has been prescribed Ozempic off-label for three years. Over that time, Tuckman said the drug has helped address the more serious PCOS complications, including her body’s excess insulin production, high blood pressure and high cholesterol. Since taking Ozempic, her blood sugar has stabilized and she’s felt less of the debilitating exhaustion that used to make lifting her head from her pillow a Herculean task.

An estimated 5 million women in the U.S. have PCOS, a poorly understood and often misdiagnosed condition that can cause women to produce excess testosterone. This can mean painful, heavy or irregular periods, infertility, excess facial and body hair, severe acne, and small cysts on the ovaries. This hormonal imbalance can also cause metabolic complications.

According to Dr. Melanie Cree, the director of the multidisciplinary PCOS clinic at the University of Colorado, women with PCOS often develop insulin resistance, which can turn into diabetes if left unchecked. The insulin resistance can also cause weight gain and make losing weight challenging, even with diet and exercise.

Doctors often prescribe another diabetes drug, metformin, to help with PCOS-related insulin resistance, though the drug works in a different way than GLP-1 agonists. Tuckman tried metformin for several years, but said it stopped working for her, which is why her doctor suggested Ozempic.

Cree is running a Phase 2/3 clinical trial of semaglutide for young women who have both PCOS and obesity. The pediatric endocrinologist is tracking the participants’ weight loss, hormone levels and menstrual cycle regularity to determine whether the drug really helps with the condition.

But because losing weight in general can help with PCOS, Cree isn’t sure if semaglutide’s effects on PCOS are separate from its effects on weight. To help answer this question, she’s planning to take a close look at the hormonal and metabolic outcomes in any women on her trial who took semaglutide, but didn’t lose much weight. If the drug improves the hormone and metabolic effects of PCOS but doesn’t cause weight loss, then the drug will have had an independent benefit for PCOS, Cree said.

“When it works, it works”

Cree is also planning another, larger PCOS trial to look more closely at whether semaglutide increases ovulation among women with PCOS.

Results from her current study are expected in the fall. Meanwhile, Cree, who also prescribes semaglutide to patients with diabetes and obesity — many of whom also have PCOS — said the personal experiences she’s heard of have been revealing.

“When it works, it works,” she said. Cree remembers one of her patients’ mothers crying during an appointment late last year. “She said, ‘You’ve given me my daughter back,’ and then everybody in the room was crying,” Cree said. “These medications are life-changing.”

Dr. Rekha Kumar, an endocrinologist at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City, cautioned that even if clinical trials do show a clear benefit, GLP-1 agonist drugs like Ozempic wouldn’t be a cure-all for women with PCOS: The symptoms can vary quite a bit, and not all women experience the metabolic symptoms most likely to benefit from GLP-1 agonists.

The drugs are also much more expensive than existing medications that address insulin resistance like metformin. “GLP-1 agonists can be used in place of metformin if patients didn’t previously respond at all to metformin or if they did not tolerate it because of side effects,” Kumar said.

Trials like Cree’s could help compile proof these drugs work for PCOS but, to secure FDA approval and widespread insurance coverage, the companies that make these drugs — in semaglutide’s case, Novo Nordisk — would need to step in and run a far larger and more expensive trial.

The company doesn’t have any plans to do so, a Novo Nordisk spokesperson confirmed via email.

“It is very unfortunate that, to my knowledge, there is no pharmaceutical company engaged in developing GLP-1 agonists for FDA-approval of a PCOS indication,” said Dr. Andrea Dunaif, an endocrinologist at the Mount Sinai Health System in New York City. “GLP-1 agonists are very promising for the treatment of PCOS in affected women with overweight or obesity.”

Cree is moving ahead with her PCOS trials anyway, though she’s concerned the widespread demand could complicate her larger trial’s expected start date, August. Since the University of Colorado has to buy the drug from Novo Nordisk for Cree to use in her trial, the shortages could affect her just as they would a patient trying to fill their prescription. According to Cree, Novo Nordisk told her the drug shortages should be resolved by August.

“It’s particularly frustrating,” she said.

Meanwhile, she’s noticed a major uptick in women with PCOS inquiring about enrollment.

Exploring other uses, including addiction

Beyond PCOS, trials are in the works to see if GLP-1 agonists can treat addiction and Alzheimer’s. Researchers are also exploring whether the drugs can help with Parkinson’s, sleep apnea and an increasingly prevalent serious condition called non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. A group of researchers in Ireland even published an intriguing, albeit very small, study in the journal Obesity showing people with obesity who took Ozempic had some immune cell improvements. These effects could, in theory, mean a better chance of fighting off cancer, though experts say the research is too early to say for sure.

In the addiction field, Joseph Schacht, an associate professor of psychiatry and substance dependence at the University of Colorado’s medical campus, is gearing up to launch a trial looking at whether semaglutide lowers alcohol cravings more than a placebo.

I’ve been working with alcohol use disorder for a long time, and there just aren’t a lot of medications that do that.

Schacht first became interested in running a trial like this when a psychiatrist colleague of his mentioned some of his patients who’d taken semaglutide for obesity had completely lost interest in alcohol.

“Hearing patients, of their own volition, stop drinking was very striking,” he said. “I’ve been working with alcohol use disorder for a long time, and there just aren’t a lot of medications that do that.”

According to Schacht, a growing collection of research in rats and mice suggest this is the case, but the human studies are still in the early days.

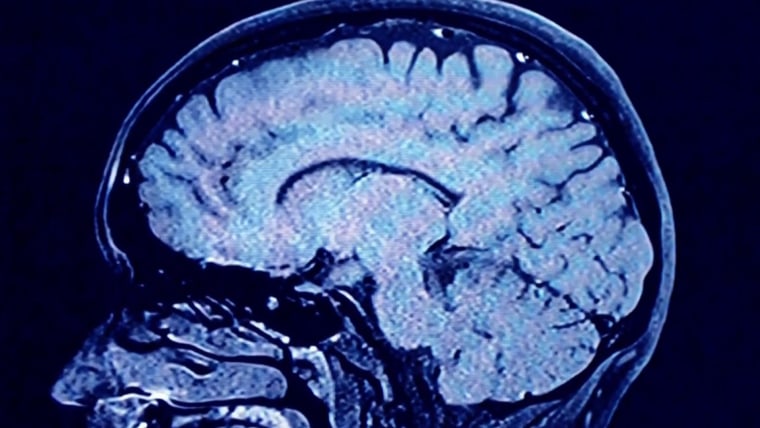

When he dove into the science behind these drugs — particularly their effects on the brain — he learned how they might work for a range of issues, from alcohol and drugs to even certain repetitive behaviors like nail biting.

In normal digestion, he explained, after someone eats, the small intestine releases the GLP-1 hormone that makes the pancreas release insulin into the blood. This insulin then lowers blood sugar, sending a signal to the brain saying the body is full and doesn’t need to eat anymore. The GLP-1 agonist drugs work by mimicking that hormone, helping to lower blood sugar while also making someone feel full.

But interestingly, Schacht said, the “I’m satisfied” feeling seems to go to the parts of the brain that regulate not only appetite, but also the desire for alcohol and drugs.

More on weight loss drugs

Leggio at the NIH is also gearing up to launch a human trial of semaglutide for alcohol use disorder by the end of the year, and expects to see a positive effect.

But without the trials, there’s no proof. And, as both Leggio and Schacht acknowledged, without the drug, there are no trials.

Like Cree with her PCOS trial, both Leggio and Schacht are concerned about having trouble securing the drug for their studies due to shortages. Novo Nordisk said in an email that it has no immediate plans to study semaglutide for alcohol use disorder.

Leggio added that even when the supply issue resolves, it will still be important for a drug company to eventually take the reins of the research, as it would have the funding and resources to carry out a large-scale clinical trial.

Drug companies step in for Alzheimer’s

There’s one condition that’s piqued Novo Nordisk’s interest enough to warrant large-scale drug trials: Alzheimer’s.

Novo Nordisk is running two clinical trials with nearly 4,000 people to find out whether semaglutide is better than a placebo at slowing cognitive decline in people with early Alzheimer’s.

According to Dr. Leila Parand, a neurologist who treats patients with Alzheimer’s at UCLA Health, past research studies suggested these drugs can help prevent damage in brain blood vessels that can lead to Alzheimer’s.

“They help preserve nerve cells and expand the growth of branches of nerve cells and help with inflammation,” Parand said. If they work, the GLP-1 drugs would be a welcome addition to the limited treatment options for Alzheimer’s.

Parand’s medical center at UCLA is one of several hundred locations where patients can enroll in one of the Novo Nordisk clinical trials of semaglutide for early Alzheimer’s. Earlier this month, she had to close enrollment early since the trial filled up ahead of schedule. According to Parand, this, too, is thanks to the skyrocketing interest in these drugs, which led many people with early Alzheimer’s to learn about the trial.

But any clear conclusions for all these potential uses of semaglutide are still years away. One of Novo Nordisk’s Alzheimer’s trials, launched in 2021, isn’t slated to end until 2026.

Other questions that researchers are still trying to answer for diabetes and obesity hang in the air, too. Do people need to take GLP-1 drugs forever? What happens when they stop? What are the long-term side effects?

“We just really don’t know,” Cree said “We don’t have the data, and there’s so much more to be learned.”Follow NBC HEALTH on Twitter & Facebook.