Pfizer’s lung cancer drug Lorbrena can extend life for patients with a rare form of the disease for years longer than other drugs, according to new research published Friday.

The drug treats a type of non-small cell lung cancer with a genetic mutation called ALK. Non-small cell lung cancers account for about 85% of lung cancer diagnoses, and ALK-positive cancers account for about 4% of those diagnoses — more than 70,000 people every year.

The cancer tends to occur in younger patients who are nonsmokers.

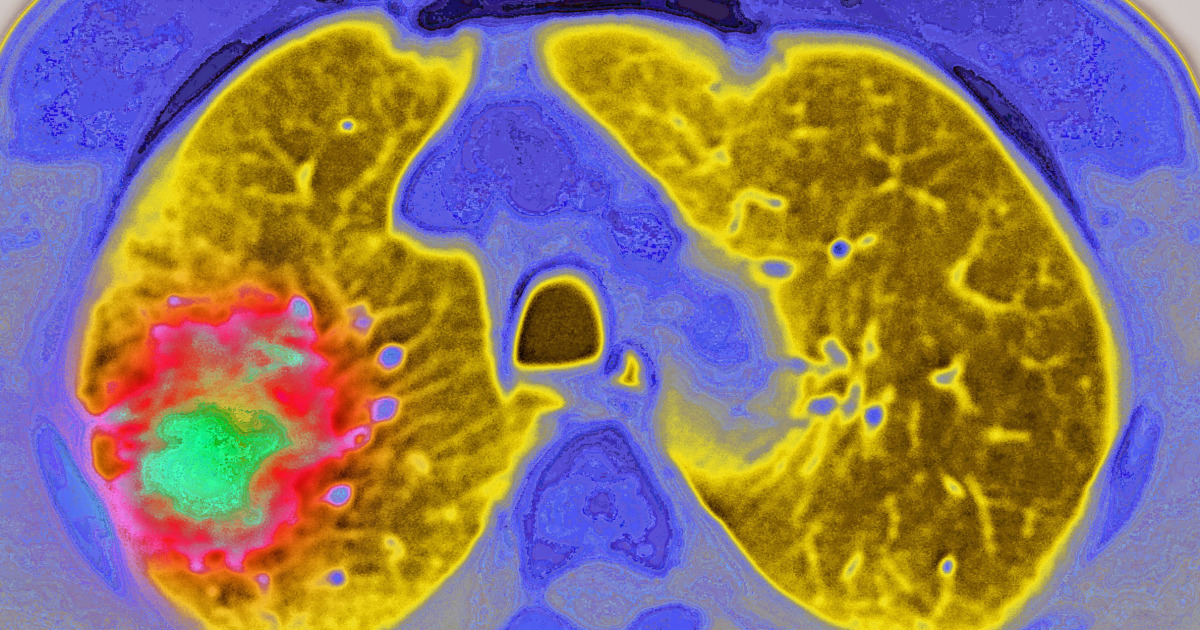

It’s also particularly deadly: ALK-positive lung cancers are especially adept at spreading to the brain. About 25% of patients have brain metastasis within the first two years of being diagnosed.

“As time moves on, that increases,” said Dr. Ben Solomon, head of lung medical oncology at the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre in Australia, who led the Pfizer-supported study.

The new research, a follow-up to a previous phase 3 clinical trial, found that after five years, 60% of patients who got Lorbrena were still alive, compared with 8% of patients who received a different drug, crizotinib (Xalkori, also from Pfizer).

The study was published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology and will be presented Friday at the American Society of Clinical Oncology’s annual meeting in Chicago.

“These results are remarkable,” said Dr. John Heymach, the chair of thoracic and head and neck medical oncology at the MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, who was not involved with the study. “For the first time, we are seeing that most patients go more than five years without their cancer progressing, and that is more than any other drug in the space. Previously, the best drugs we had were two to three years.”

There is one caveat: The drug that Lorbrena was compared to, crizotinib, is no longer used in the U.S., said Dr. Julie Gralow, the chief medical officer and executive vice president at the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Both drugs — part of a class of medications called tyrosine kinase inhibitors — fight tumor cells in generally the same way. However, crizotinib is a first-generation version of this type of drug, whereas lorlatinib (the generic name for Lorbrena) is the third generation.

The current standard of care, meaning the drugs oncologists typically use to treat ALK-positive lung cancers, includes Lorbrena and two second-generation drugs: brigatinib (Takeda’s Alunbrig) and alectinib (Genentech’s Alecensa).

“In an ideal world, we would have compared lorlatinib to one of those, but the study was started before those were approved,” Gralow said.

Still, “this is the best long-term data we’ve ever seen for” this class of drugs, she said. “This is just the most impressive progression-free survival we’ve ever seen in this population.”

The new study also found that the patients taking Lorbrena were nearly 95% less likely to have their cancer spread to their brain than those taking crizotinib. Four of the 114 patients taking Lorbrena developed brain metastasis within about 16 months, compared to 39 out of the 109 taking crizotinib, a huge feat for people living with ALK-positive lung cancer.

“Earlier drugs like crizotinib were not effective at blocking the spread in the brain,” Heymach said. While alectinib and brigatinib do have some ability to block tumors from spreading to the brain, he added, “the activity we’re seeing in the brain for lorlatinib is really unprecedented.”

The reason Lorbrena is so effective at preventing and treating brain metastasis is its ability to cross a membrane called the blood-brian barrier and enter the brain, something not all drugs can do.

“When the cancer spreads to the brain, that often leads to a marked decline in quality of life and really horrible side effects,” Heymach said.

Only a trial that compares all three standard-of-care drugs head to head, rather than to crizotinib can determine which is superior, said Dr. Isabel Preeshagul, a thoracic medical oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City.

However, “it does seem that lorlatinib may have an edge in regards to CNS efficacy,” Preeshagul said, referring to the drug’s ability to treat and prevent spread to the brain. “This was a big unmet need for patients that harbor” the ALK mutation.

With its exceptional ability to cross into the brain comes the potential for more side effects, said Dr. Aaron Mansfield, a medical oncologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.

People taking Lorbrena may be more prone to memory or mood issues compared to those taking similar second-generation drugs.

Solomon, the study leader, said because of this, the drug might not be the best choice for people with psychiatric disorders.

But a lower dose may be able to remedy the drugs’ neurotoxicity.

“We know that reducing the dose is very effective at reducing the cognitive side effects, and in those patients, outcomes were just as good as those that didn’t lower the dose,” Solomon said.

All four tyrosine kinase inhibitors only work in people who have ALK-positive lung cancer, not other types of lung cancer. While most mutations are caused by a single change in a gene, the ALK-positive mutation occurs when two genes break and then fuse together. Because of this, it’s sometimes referred to as ALK fusion.

Preeshagul said it’s important for patients diagnosed with lung cancer to advocate for themselves and ask for further testing to determine if they have the mutation, which is missed without additional tests.

“If you are diagnosed with stage 4 lung cancer, it’s important to ask your oncologist to send off next-generation sequencing,” she said. “If you have an ALK fusion, you should absolutely be on targeted therapy. The treatments that we have are life-altering.”