The summary

- Japan has reported a record number of cases of streptococcal toxic shock syndrome, a rare and dangerous bacterial infection caused by Group A strep bacteria.

- The U.S. similarly saw serious Group A strep infections — including STSS — reach a 20-year high in 2023.

- Experts think a post-pandemic rebound of bacterial and viral infections could partially explain the trend, but many unanswered questions persist.

A record-breaking rise in potentially fatal infections in Japan is bringing attention to persistent, unanswered questions about the group of bacteria behind the illnesses.

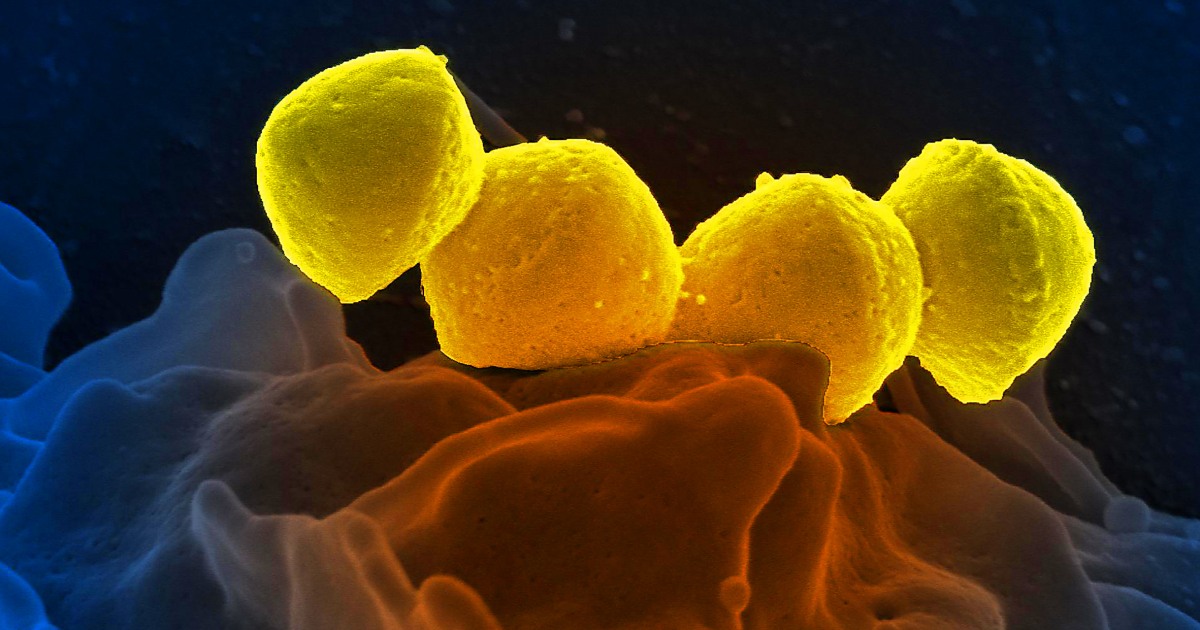

The rare infection, streptococcal toxic shock syndrome (STSS), is caused by Group A strep bacteria, the same type that causes strep throat and scarlet fever. In rare cases, Group A strep can enter deep tissue or the bloodstream, as is the case with STSS.

Up to 30% of STSS infections are fatal: The condition usually starts with a fever, chills, muscle aches, nausea or vomiting but can become life-threatening in 24 to 48 hours if left untreated. It can occur in tandem with necrotizing fasciitis, another bacterial infection that is described as “flesh-eating” because it destroys the soft tissue under the skin.

So far this year, Japan has recorded at least 1,019 cases of STSS, according to a report released earlier this week by the country’s National Institute of Infectious Diseases. That’s its highest total ever, already larger than last year’s record tally of 941.

The unprecedented numbers are renewing focus on the mysterious recent behavior of Group A strep bacteria, which has circulated at unusually high levels over the past few years in both the United States and Japan, resulting in a surge of life-threatening and sometimes fatal infections. Disease experts don’t fully understand why that’s happening yet.

In the U.S., the number of serious Group A strep infections — including STSS — reached a 20-year high in 2023, according to preliminary data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This year, the CDC has recorded 395 cases of STSS as of June 8, exceeding last year’s total of 390 with many months to go. The agency noted, though, that Group A strep activity has decreased in the last several months, as is expected at this time of the year.

The United Kingdom also saw an outbreak of severe Group A strep infections in late 2022, then recorded more cases than average from September to February, as well.

Disease experts have attributed the trend, in part, to the broader post-pandemic rebound of common viral and bacterial infections — including strep. During the period when people were avoiding in-person interactions, such pathogens had fewer opportunities to spread. Now, people may be more susceptible again.

“This may be part of this global phenomenon: the comeback of strep,” said Dr. William Schaffner, an infectious diseases expert at Vanderbilt University Medical Center. He added: “Most of these infections were really profoundly reduced during Covid because we stayed at home and wore masks and closed schools and the like.”

However, other viral illnesses that surged as lockdowns eased and socializing resumed have seemingly returned to their baselines, whereas strep cases continue to surpass the usual averages, experts said.

“Any number of infections have come back to normal, conventional levels — but strep has exceeded them. Exactly why that’s happening we don’t know,” Schaffner said.

Complicating the picture is the fact that Group A strep infections were rising in the U.S. for several years before Covid emerged.

So experts think there’s probably more to the explanation than the pandemic. Has the bacteria evolved to cause more severe illness? Are there any unidentified associations between Group A strep and certain viral infections? Are some age groups getting sick now who weren’t in years past? Answers have yet to be determined.

As for who is at risk of STSS, older adults and people with diabetes are generally more vulnerable, and sores from chickenpox or shingles also make people more likely to contract it. That’s because Group A strep can enter the body through open wounds and develop into toxic shock syndrome from there. Experts also think that some viruses may predispose people to secondary bacterial infections by damaging the airways or weakening the immune system.

But in many cases, disease experts aren’t able to determine how a particular person got sick.

“When a patient comes in with group A strep in the blood, unless they have a wound, you often don’t know how it got into the body,” said Dr. Lee Harrison, a professor of medicine and epidemiology at the University of Pittsburgh.

Although a particular country’s level of baseline immunity to the bacteria, or perhaps even certain genetic traits, may influence a population’s susceptibility, Japan’s situation is a reminder to doctors everywhere to monitor for severe strep infections, said Dr. Amesh Adalja, an infectious disease physician and a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security.

“What happens in Japan is important for other countries just to be on alert,” he said.

Such awareness is crucial because patients with STSS should be treated as soon as possible after symptoms appear — that may involve antibiotics or a surgery to remove infected tissue.

No vaccine for Group A strep is available, though several are in development, including one that seemed safe in a phase 1 trial. Harrison said the recent rise in infections in Japan and the U.S. could accelerate demand for this research.