Toxic bacteria have been detected in several bodies of water in Utah’s Zion National Park, the National Park Service announced this week.

Three bodies of water in the park have cyanotoxins in them, according to the Park Service: the North Fork of the Virgin River, North Creek and La Verkin Creek. These toxins are produced by a type of bacteria called cyanobacteria, also known as blue-green algae.

The algae is common in ponds and lakes and not always dangerous, but it can grow into large blooms that produce cyanotoxins. In people, symptoms of cyanotoxin exposure include irritation in the eyes, ears, nose, throat or skin, as well as headache, seizures, vomiting and diarrhea. In animals and pets, symptoms include drooling, low energy, lack of appetite, paralysis and vomiting.

In very rare cases, cyanotoxin poisoning can be fatal.

The NPS has advised visitors against swimming or submerging their heads in the affected Zion waterways and warned people not to drink water from anywhere in the park. The watches and warnings extend to popular areas of the park, including The Narrows and Emerald Pools.

If exposed, people should seek immediate medical attention and call poison control or 911, the NPS said.

The NPS attributed the blooms in Zion to an extended period without floods, which has allowed cyanobacteria to grow rapidly and unchecked.

Climate change and pollution play a role in the proliferation of cyanobacteria, according to Ramesh Goel, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of Utah.

Human activity pollutes water with nitrogen and phosphorus, which then fuel the growth of blue-green algae, Goel said. Fertilizer runoff and lingering pollutants in wastewater processed in treatment plants both send excess nutrients into rivers and lakes, he said.

“In states like Utah, you have the snow melting, and the snow melting from watersheds brings more nutrients to the water,” Goel said.

Rising temperatures across the country — which research suggests are linked to climate change — also create optimal conditions for the bacteria to grow, he added.

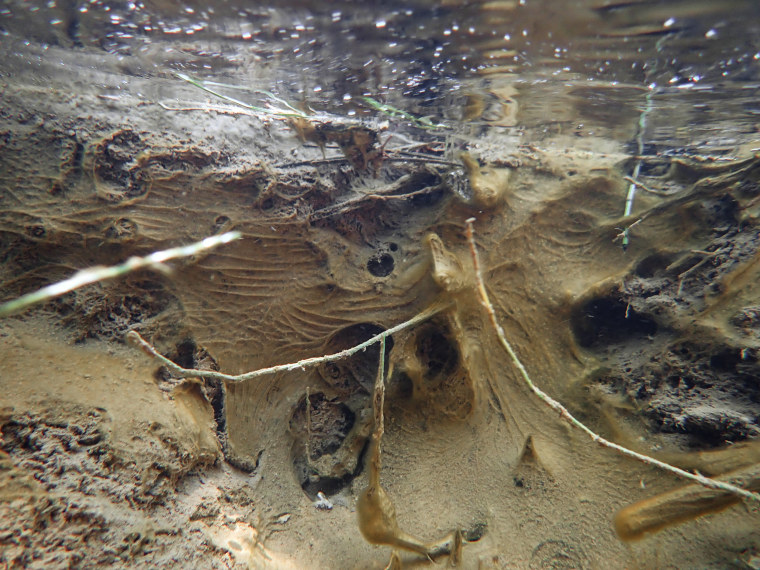

In lakes and reservoirs, cyanobacteria look like blue-green paint floating on the water’s surface, according to David Stevens, professor of civil and environmental engineering at Utah State University. But in rivers, like the Virgin River currently affected in Utah, the bacteria often grow on rocks around the water and can look like slimy mud.

Even getting clothing wet counts as exposure, Stevens said.

“It doesn’t matter if you have a shirt on or something like that because once your shirt’s wet, it’s no different than having a bare arm,” he said. “Just stay away from the water, and you’ll be fine.”

Anyone who comes into contact with contaminated water should immediately wash that area of their body with soap and water, Stevens added.

In the past month, local health officials have issued warnings about cyanotoxin detections in waterways in Montana, Oregon and Minnesota, among other states. Last month, over 50 beaches were closed for swimming in Massachusetts due to excess bacteria, some of which was cyanobacteria. In 2018, toxic blooms of blue-green algae caused a smell in parts of Southwest Florida that persisted for months.

Stevens said another reason for the increasing presence of cyanotoxins is that people are building more houses along lake shores and discharging septic systems into the water, which leads to less clear, more algae-ridden lakes. Livestock and wild animals can also pollute water with their waste, he added.

Cyanobacteria are among the oldest microorganisms on the planet.

“They’ve been here millions of years and they’re thrived under lots of different conditions,” Stevens said. “What we need to do is make sure we don’t create conditions that are going to cause toxic problems.”