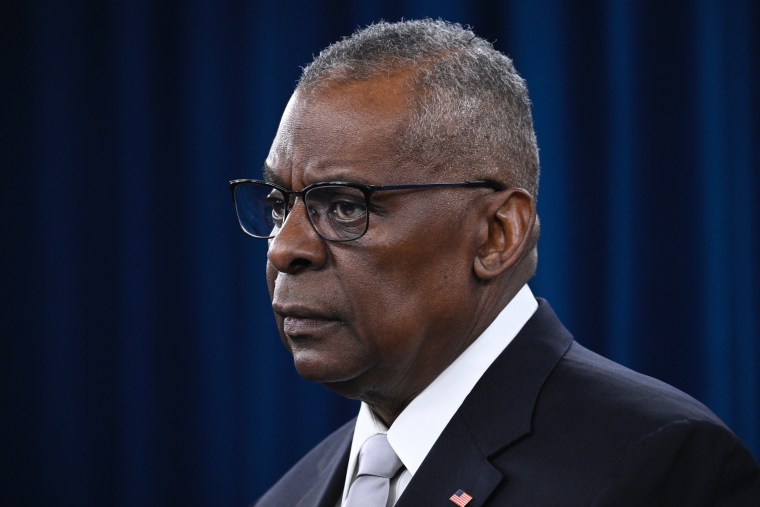

Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin apologized this week for not being more transparent about his prostate cancer diagnosis, acknowledging that the news had not only affected him but also shocked many others, “especially in the Black community.”

“It was a gut punch,” Austin said Thursday at a news briefing.

The diagnosis — which was made public Jan. 9, about a week after he had been hospitalized with complications from cancer surgery, blindsiding even the White House — has renewed public discussion around prostate cancer in the Black community.

Why does it appear to be so prevalent in black men, how soon is too soon to seek screening, what are the early symptoms and when is an appropriate time to tell loved ones?

All men are at risk for prostate cancer, the second most common cancer among men in the U.S., according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The American Cancer Society estimates that in 2024, there will be nearly 300,000 new cases of prostate cancer and just over 35,000 deaths.

Whether prostate cancer is, in fact, more common in Black men than other groups remains an open question, said Dr. Abhinav Khanna, a urologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.

But it is sometimes more aggressive in Black men, he said.

Black men in the U.S., Khanna said, are two times more likely to die from prostate cancer than white men.

“Not all prostate cancer is lethal, but we have seen that black men do have a higher risk of dying from prostate cancer,” he said.

One potential reason is that Black men — depending on their socioeconomic status — may not get screened as vigilantly as white and Asian men do in the U.S., leading to more advanced cancer diagnoses and worse outcomes, said Dr. Ravi Munver, vice chairman of the department of urology at Hackensack University Medical Center in New Jersey.

A study published in the journal Cancer in 2022, for example, found that outcomes for Black men with prostate cancer are worse because they are less likely to be screened or to receive treatment.

Dr. Adam Murphy, an associate professor of urology at Northwestern Medicine in Chicago, said genetics can also play a role in prostate cancer risk.

Being of West African descent, for example, is a potential risk factor, Murphy said. Other risk factors include age and family history, he said.

“If you have first-degree relatives who have prostate cancer, or even secondary-degree relatives, it increases your risk a little bit,” he said. “And then there are related cancers that run in families like breast cancer, ovarian cancer, and other germline genetic mutations that can increase your risk, like Lynch syndrome.”

What are symptoms of prostate cancer?

For the vast majority of men, there won’t be any signs or symptoms until the disease is far more progressed, experts said. Dr. Samuel Haywood, urologic oncologist at Cleveland Clinic, said symptoms include:

- Difficulty urinating

- Blood in urine

- Pain near the prostate

Before symptoms begin to appear, the only screening for prostate cancer is a blood test called a prostate-specific antigen, or PSA. In 2018 the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended that men ages 55 to 69 should make an individual decision whether to get a PSA test. The task force advised against prostate cancer screening for men 70 and older.

Munver recommended that Black men who are at increased risk for prostate cancer should start screening at ages 40 to 45, aligning with recommendations from the American Urological Association.

“If it’s caught early, prostate cancer is very treatable, very curable,” said Khanna.

Munver understood why Austin didn’t tell the public about his diagnosis sooner.

Prostate cancer is a very sensitive issue for men, he said. It’s often only after they are diagnosed, or come to terms with their diagnosis or undergo treatment, that men are more comfortable talking about their diagnosis, he said.

“It’s a very personal issue,” he said. “They realize that prostate cancer is one of the cancers that’s very treatable or curable in men and not necessarily a death sentence.”

Murphy, of Northwestern Medicine, noted that there is also a stigma for men generally.

“The way that men engage with health care is very different than what women do because of a lack of having to go into see OB-GYN,” he said. “And so men are oftentimes lost after they graduate from high school or college.”

“I think what his action did was to kind of highlight the fact that even though he was duty bound to tell that fact, you know, to the White House, that same stigma persisted, that’s how strong it was,” Murphy said.